Archive for the ‘economy’ Tag

Sick with swine flu racism

The threat of a deadly swine flu pandemic appears to be fading, despite an outbreak of hype that one former CNN reporter says stemmed from the media’s “economic vested interest in promoting the fear.”

But fear may well be lingering — fueled by animosity toward Mexicans — thanks to a rash of comments from some of America’s nastiest right-wing broadcast personalities.

Ignoring news reports that some swine flu victims inside the U.S. likely contracted the virus during recent trips to Mexico, Fox News regular Michelle Malkin asserted: “I’ve blogged for years about the spread of contagious diseases from around the world into the U.S. as a result of uncontrolled immigration.”

“No contact anywhere with an illegal alien!” radio host Michael Savage warned listeners about the contagion threat. “And that starts in the restaurants,” he said, where you “don’t know if they wipe their behinds with their hands.”

As Media Matters for America reported, radio host Neil Boortz stoked fears of a “bioterrorist” plot, asking, “What better way to sneak a virus into this country than to give it to Mexicans?”

Savage also ran with that idea: “There is certainly the possibility that our dear friends in the Middle East cooked this up in a laboratory somewhere in a cave and brought it to Mexico knowing that our incompetent government would not protect us from this epidemic because of our open-border policies.” He suggested terrorists may realize that Mexicans “are the perfect mules for bringing this virus into America.”

Rush Limbaugh ranted about an Obama administration conspiracy to use both the swine flu scare and the renewed debate over torture “to cover up the mess that is the United States of America right now.” (One wonders if he’s including Dick Cheney’s prominent role in the latter.)

Rush Limbaugh ranted about an Obama administration conspiracy to use both the swine flu scare and the renewed debate over torture “to cover up the mess that is the United States of America right now.” (One wonders if he’s including Dick Cheney’s prominent role in the latter.)

While such ugliness from this bunch is predictable, it’s worth remembering that these folks have sizeable to large audiences. Moreover, the rank xenophobia underscores an uneasy truth: America has yet to contend in a serious way with its enormous immigration problem.

Obama continues promising to do so, as when he campaigned for president. The task, like many others since last fall, has been swallowed up in the nation’s economic maelstrom — but it’s inextricable. (So is overhauling health care in Obama’s view.) As Colin Powell emphasized when I interviewed him back in 2007 — not long after immigration had commanded headlines in a national election cycle — dealing with the issue is at once a moral and economic imperative. In an hour-long conversation covering much political ground, Powell’s comments on the matter stood out. We should do everything we can, he said, to admit people legally, dry up the flow of illegals and defend our borders. “But let’s recognize that these folks, whether legal or illegal, are making an enormous contribution to America’s well-being. They do the jobs that others don’t want to do.”

He continued: “It’s outrageous for us to take advantage of this population of 12 million people, to use them to cut our grass and build our houses and repair our streets, but keep them illegal and subject to deportation. That’s not equitable — that’s not America. We have to find a dignified way to work through with this population.”

With the swine flu scare, the unpleasant opportunism of the far right reflects how incredibly far we still have to go.

On Mark Bowden’s NYT takedown

The so-called crisis in the news industry sure has generated some sensational stories of late. “American journalism is in a period of terror,” announces Mark Bowden in a tome of an article appearing in the May issue of Vanity Fair. Mostly a deft hatchet job on Arthur Sulzberger Jr., the publisher of the New York Times, Bowden’s piece sent the media cognoscenti into a tizzy, although nobody seems to have noticed its one truly illuminating segment.

Photo illustration from Vanity Fair.

Even the mighty Times is facing financial peril these days, and Bowden’s premise is that the newspaper scion “has steered his inheritance into a ditch.” He abuses tools of the trade to help suggest his case. As one unnamed “industry analyst” tells us, “Arthur has made some bad decisions, but so has everyone else in the business. Nobody has figured out what to do.” Earth shattering. Perhaps Bowden should pick up a copy of the Times and read Clark Hoyt on the suitable use of anonymous sources. For a substantive take on contemporary debacles across the business, check out this recent piece by Daniel Gross.

In fact, I’m a big fan of Bowden’s. Right now I happen to be reading his 2006 book “Guests of the Ayatollah,” a riveting account of the Iran hostage crisis. Particularly in the realm of national security, few reporters are as exhaustive, persuasive — and downright exciting to read — as him.

On the media, not so much. There he has tended toward the self-involved, maybe a particular pitfall for great reporters covering their own vocation. (See the opening line of the Sulzberger article, which zooms in directly on… Bowden himself, as he receives a phone call from Sulzberger: “I was in a taxi on a wet winter day in Manhattan three years ago…” Especially telling, I think, given that in another recent piece orbiting the news business, a profile of David Simon, Bowden also wrote himself prominently into the narrative.) The Vanity Fair article is exquisitely timed with the accelerating upheaval in the newspaper industry, and reads mostly like, well, a salacious, insider-y Vanity Fair article.

And yet, buried deep in the 11,500 words is one of the best analogies I’ve encountered anywhere conveying the potential for digital journalism:

When the motion-picture camera was invented, many early filmmakers simply recorded stage plays, as if the camera’s value was just to preserve the theatrical performance and enlarge its audience. To be sure, this alone was a significant change. But the true pioneers realized that the camera was more revolutionary than that. It freed them from the confines of a theater. Audiences could be transported anywhere. To tell stories with pictures, and then with sound, directors developed a whole new language, using lighting and camera angles, close-ups and panoramas, to heighten drama and suspense. They could make an audience laugh by speeding up the action, or make it cry or quake by slowing it down. In short, the motion-picture camera was an entirely new tool for storytelling.

Bowden uses the comparison in the service of whacking Sulzberger — but it also points directly to a broader stagnation in media companies’ use of the digital platform. There is experimentation going on, but often without much imagination: Digital video clips are all the rage? OK, we’ll put reporters on camera describing the stories they’ve just published! Online communities and reader interactivity are the latest buzz? OK, we’ll feature the shouting matches in our comments threads as actual news!

The rising multimedia and publishing capabilities of the digital realm are charged with promise, and demand deeper thinking about their optimal use. With any given subject, which digital tools are most effective for gathering information and telling the story? How can the information-rich ecosystem of the Web enhance the knowledge gained? What new ways are there to produce reliable, authoritative and compelling content, taking maximum advantage of a decentralized and participatory technology like no other we’ve ever known?

Soon enough we may all be getting our news on a kind of flexible digital paper. The possibilities for what it could contain are big, and they’re just beginning.

UPDATE: Mark Bowden responds.

Waking up to America’s economic nightmare

With the roughly 1,500-point rise in the Dow Jones average since early March, it seems investors have been dreaming about the good old days. This Bloomberg chart from last Thursday’s trading marks the apparent disconnect — you don’t have to be a stock market maven to sense that the dramatic rally will likely prove to be, in the parlance of Wall Street, the kaput kitty hitting the pavement.

With the roughly 1,500-point rise in the Dow Jones average since early March, it seems investors have been dreaming about the good old days. This Bloomberg chart from last Thursday’s trading marks the apparent disconnect — you don’t have to be a stock market maven to sense that the dramatic rally will likely prove to be, in the parlance of Wall Street, the kaput kitty hitting the pavement.

Take your pick of grim indicators. For the last two months the Consumer Confidence Index has plumbed its lowest depths since its inception in 1967. As we learned Friday, the nation lost another 663,000 jobs in March, bringing the total to 5.1 million since the recession began in December 2007. Unemployment may be a lagging economic indicator, but there’s little to suggest that the wave is cresting or will be any time soon.

But the worst sign of all right now may be this: America is still stuck in the anger stage. Recently I overheard a classic strain of the outrage in a coffee shop in Noe Valley (hardly ground zero for hard times), in a conversation between two rather comfortable looking middle-aged adults. One was wailing away on America’s preferred punching bag, Mr. Wall Street Executive, for “raping the taxpayers” without remorse. His hair was so on fire that I feared his head might actually explode. Soon the talk hit on the hypocrisy of the Obama administration’s forcing General Motors chief Rick Wagoner to fall on his sword while Wall Street’s lords of finance so unfairly kept feasting on federal bailout funds. Somehow the disastrous story of the SUV-bloated American auto industry didn’t come up.

Indeed, we must also be in a recession of genuine awareness. While New York Times columnist Frank Rich can himself be shrill at times, he’s got it right regarding the continuing blame game:

Why is there any sympathy whatsoever for a Detroit C.E.O. who helped wreck his company, ruined investors and cost thousands of hard-working underlings their jobs, when there is no mercy for those who did the same on Wall Street? Might we, too, have a double standard? Could we still be in denial of the reality that greed and irresponsibility were not an exclusive Wall Street franchise during our national bender?

A prominent financial expert I interviewed last week for a forthcoming magazine piece on the economic crisis said to me at one point in our conversation, “Almost everybody who was part of the system failed.” He wasn’t only talking about Wall Street institutions, government regulators and the media.

Easily enough we get whipped into a frenzy over unjust executive bonuses or the sins of the media’s prime time ding-dongs. But what of America’s common financial lifestyle over the last two decades? As Rich continues, in answer to his own question: “Any citizen or business that overspent or overborrowed in the bubble subscribed to its reckless culture. That culture has crumbled everywhere now, and a new economic order will have to rise from its ruins.”

Even better put, it will have to be built from them. That will be painstaking, no doubt — block by block, brick by brick, as has been said by a certain someone. But right now, it seems, too many people are still standing on the outskirts shouting about who plundered the village, rather than heading into the collective rubble and really starting to pick up the pieces.

UPDATE: On a related note, Wall Street conspiracy theorists and/or Hollywood screenwriters will find plenty of grist in this Times front-pager on Larry Summers’ enriching hedge fund days at D.E. Shaw prior to joining Team Obama:

D. E. Shaw does not like to talk about what goes on inside its modish headquarters near Times Square. There, esoteric trading strategies are imagined, sketched on whiteboards and modeled on supercomputers by an elite corps of math wizards and scientists, most of them unknown to the outside world….

At Shaw, Mr. Summers, the professor, was often the student. The arrogant personal style that turned off some Harvard colleagues seemed to evaporate, Shaw traders say. Mr. Summers immersed himself in dynamic hedging, Libor rates and other financial arcana.

He seemed to fit in among Shaw’s math-loving “quants,” as devotees of math-heavy quantitative investing are known. Traders joked that Mr. Summers was the first quant Treasury secretary because he had once ordered dollar bills to be printed with the transcendental number pi — 3.14159… — as the serial number.

Paging Dan Brown and Ron Howard?

Seeing Obama’s burden, the drug war and more

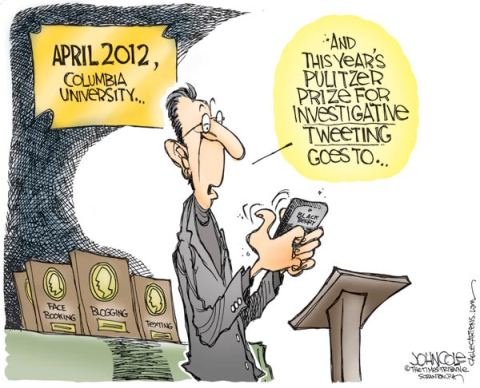

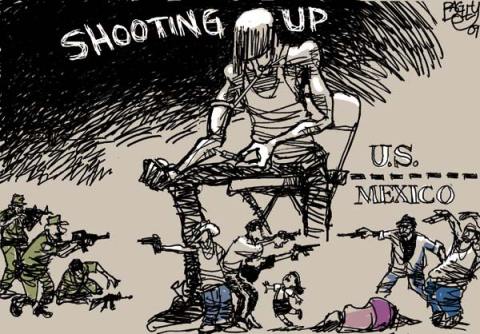

Even in the loquacious realm known as the blogosphere, it is possible at times to lack words. Or to feel that there are simply too many of them. Either way, Daryl Cagle’s Political Cartoonists Index offers a pleasing alternative. Here are three recent entries that caught my eye.

Hajo (Amsterdam), on President Obama’s economic travails:

John Cole (Scranton, PA), peering into journalism’s truncated future:

Pat Bagley (Salt Lake City), a potent take on the Mexican-American drug war:

The month the news broke

It may be that we’ll look back at March 2009 as a pivotal time in the erratic but inexorable transition from print to digital news. In some ways it’s very much a slow-motion revolution, beginning perhaps as long ago as 1981, and far from over. But this month has been striking both for the destruction in the newspaper industry and the hum of activity focused on the digital future.

It’s the latter that matters more. NYU media maven Jay Rosen has pulled together an essential roundup for anyone interested in diving deep into the discussion. Rosen credits a March 13 essay by Clay Shirky with triggering a flurry of writing; he summarizes a dozen recent pieces that build out the picture. I haven’t read them all yet, but in addition to Shirky’s piece I highly recommend Steven Berlin Johnson’s Old Growth Media and the Future of News, which he presented at the South By Southwest Interactive Festival in Austin. His use of ecosystems as a metaphor for the digital transformation is enlightening in multiple ways, while smartly avoiding utopianism:

It’s the latter that matters more. NYU media maven Jay Rosen has pulled together an essential roundup for anyone interested in diving deep into the discussion. Rosen credits a March 13 essay by Clay Shirky with triggering a flurry of writing; he summarizes a dozen recent pieces that build out the picture. I haven’t read them all yet, but in addition to Shirky’s piece I highly recommend Steven Berlin Johnson’s Old Growth Media and the Future of News, which he presented at the South By Southwest Interactive Festival in Austin. His use of ecosystems as a metaphor for the digital transformation is enlightening in multiple ways, while smartly avoiding utopianism:

Now there’s one objection to this ecosystems view of news that I take very seriously. It is far more complicated to navigate this new world than it is to sit down with your morning paper. There are vastly more options to choose from, and of course, there’s more noise now. For every Ars Technica there are a dozen lame rumor sites that just make things up with no accountability whatsoever. I’m confident that I get far more useful information from the new ecosystem than I did from traditional media a long fifteen years ago, but I pride myself on being a very savvy information navigator. Can we expect the general public to navigate the new ecosystem with the same skill and discretion?

Indeed, as Johnson suggests, information consumers may yet crave the guidance of authoritative institutions, including… newspapers. Some of which now command some of the largest online audiences. But many of them have been failing in the vision department, as Alan Mutter pointed out early this month:

As a direct consequence of the breakdown in the traditional media business model, publishers today are cutting the quality and quantity of the content they produce at the very moment they should be investing more aggressively than ever … As the most challenged of all the distressed media companies, newspapers are so strapped today that they are producing ever less original reporting … This is not merely a step in the wrong direction. It is a leap into the abyss.

As the fresh experiment with The P-I in Seattle seems to indicate so far, taking a newspaper all-digital while cutting its news gathering capacity by roughly 80 percent is not a great way to proceed.

While there is still plenty of handwringing going on, in my view the essays gathered by Rosen evoke daybreak far more than twilight. And March 2009 is ending on a bright note, at least symbolically. Ever since its election-year rise, the opinion-laden Huffington Post has been touted as a model for future journalism — never mind that it doesn’t pay most contributors and produces almost zero original reporting. Late yesterday the publication announced a new turn: the launch of a $1.75 million investigative reporting initiative.

Could marijuana light up the economy?

The debate about whether to legalize marijuana in the United States has never been a mainstream one. So it’s been fascinating to watch how much attention the concept has gotten lately, however viable it may or may not be.

Preoccupation with Mexico’s violent drug war is one factor; marijuana is the largest source of revenue for the cartels’ multibillion dollar business north of the border. Commodify the major cash crop through legalization, the idea goes, and its cost will plummet, putting a serious dent in the bad guys’ bank accounts.

But the larger issue lighting up the idea seems to be the battered American economy. In February, California state lawmaker Tom Ammiano proposed legislation that would regulate the cultivation and sale of marijuana, with a potential tax windfall of more than $1 billion to help bail out the state from a severe budget crisis.

But the larger issue lighting up the idea seems to be the battered American economy. In February, California state lawmaker Tom Ammiano proposed legislation that would regulate the cultivation and sale of marijuana, with a potential tax windfall of more than $1 billion to help bail out the state from a severe budget crisis.

On Thursday, the legalization concept wafted all the way up to the presidential level. In a live Internet “video chat” with Americans, President Obama found himself responding to a question that had been voted among the most popular of those submitted by the public: whether the controlled sale and taxation of marijuana could help stimulate the U.S. economy. “I don’t know what this says about the online audience,” Obama quipped. “The answer is no, I don’t think that is a good strategy to grow the economy.” By Thursday night, CNN’s Anderson Cooper was jabbering at length about the idea with law enforcement officials.

The issue of taxation just cropped up in another intriguing way. The Drug Enforcement Administration caused a stir in San Francisco on Wednesday when it raided a locally permitted medical marijuana dispensary. In part there was outcry because just days prior U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder had announced that the feds would no longer prosecute medical marijuana dispensaries where they are allowed under state and local law. So why the bust now?

So far the DEA isn’t sharing any details, but according to the San Francisco Chronicle, “A source in San Francisco city government who was informed about the raid said the DEA’s action appeared to be prompted by alleged financial improprieties related to the payment of sales taxes.”

It’s difficult to gauge the Chronicle’s anonymous source, but if accurate, the explanation seems rather odd. Last I checked, there was no national sales tax in the United States, so why would the federal government be interested in that issue? Moreover, while I’m not sure whether it applies to medical marijuana, prescription drugs are exempt under the current California sales tax regime.

The federal government does oversee interstate commerce, and U.S. border security, of course — perhaps better clues to the DEA’s continuing interest in the case. (Was supply at the SF pot club the real issue?) Which takes us back to the headline-grabbing drug war. You don’t have to stare for long at this DOJ threat assessment map tracking the Mexican cartels to notice the densely covered trajectory that runs the length of I-5, from San Diego to San Francisco to Seattle.

Is AIG evil? Let’s hear from the people!

At hearings Wednesday on Capitol Hill lawmakers excelled at one of the things they do best: political theater. The outrage flowed, as Edward Liddy, the current CEO of American International Group, got grilled about the $165 million in bonuses going to a bunch of guys who helped bring the U.S. banking sector to the brink of collapse with immense and immensely reckless insurance bets. (A complicated scheme, but credit to President Obama, who did a decent job Wednesday morning of explaining in basic terms how they did it.)

To what degree Americans should be angry at taxpayer-backed AIG or our government leaders (past and present) is a murky discussion, but it’s clear that the level of outrage across the country is plenty high right now. (High enough not only to juice a show on Capitol Hill, but also some widely celebrated media blood sport.) What’s interesting to me at the moment is how a number of major news outlets have seen the popular discontent as an opportunity to highlight reader interactivity on the Web.

At the top of its home page Tuesday night the New York Times featured reader diatribes — treating them as news itself. “Some people are vengeful, calling for jail, public humiliation or even revolution,” reported A.G. Sulzberger. Over the last few days, “the most passionate voices, not surprisingly, could be found on the Internet — on blogs and discussion threads — in unusually bountiful numbers.”

On Wednesday afternoon, the Washington Post featured a round-up of its own reader comments, if not especially articulate or enlightening. (“Corporate and political self-seeking are devastating our families, our country, and out [sic] world.” Etc.) The Wall Street Journal’s home page gave top real estate to voices from the “Journal Community,” which tended, naturally, to reflect a constituency of a somewhat different kind. “The Obama administration is spending too much time and resources to go after this money,” scolded reader Craig Cohen. “The fact is, it will probably cost the US more money in legislative time, attorney fees, opportunity cost, etc to get these bonuses back than they are worth. But that doesn’t matter to the President. This is not about bonuses. It’s about class warfare. These bonuses went to the elite…. They must be punished!”

A key question on my mind is, how can media companies unlock greater potential with reader engagement and participation? It’s stating the obvious to say that there’s nothing cutting-edge at this point about letting readers loose with their opinions. (Put nicely, it tends to have limited value in unfiltered form.) Are there new ways to generate useful insight and information from the many smart readers out there, rather than just a lot of noise? This is an issue we grappled with regularly over the years when I was at Salon, and I have a hunch it could figure prominently in ways forward with news reporting in the rising digital realm. What if, for example, readers with experience in the culture of Wall Street could begin to add to the picture of how the AIG problem metastasized? Or shed light on how thoroughly it has been reported on?

Smart people have been working on ideas in this area for some time. Mother Jones has an interesting activist-style approach that it’s experimenting with. Between the ongoing destruction in the newspaper industry and what some major companies are attempting now online in terms of reader interactivity (the two hardly unrelated), I have the sense that whoever begins to unlock the challenge in a more creative, substantive way could make a big splash.

The revolution will be further digitized

A large newspaper in a major American city has just gone all-digital. Depending on how you choose to look at it, the occasion is either tragic or revolutionary.

The 146-year-old Seattle Post-Intelligencer printed its last edition on Tuesday, becoming an Internet-only news source. In a report on its own Web site, the “paper” described the contours of the new, much smaller operation now in place. The P-I, as it’s called, is a “community platform” that will feature “breaking news, columns from prominent Seattle residents, community databases, photo galleries, 150 citizen bloggers and links to other journalistic outlets.” The New York Times notes that The P-I “will resemble a local Huffington Post more than a traditional newspaper,” with a news staff of about 20 people rather than the 165 it had, and with an emphasis more on commentary, advice and links to other sites than on original reporting.

The 146-year-old Seattle Post-Intelligencer printed its last edition on Tuesday, becoming an Internet-only news source. In a report on its own Web site, the “paper” described the contours of the new, much smaller operation now in place. The P-I, as it’s called, is a “community platform” that will feature “breaking news, columns from prominent Seattle residents, community databases, photo galleries, 150 citizen bloggers and links to other journalistic outlets.” The New York Times notes that The P-I “will resemble a local Huffington Post more than a traditional newspaper,” with a news staff of about 20 people rather than the 165 it had, and with an emphasis more on commentary, advice and links to other sites than on original reporting.

The P-I venture may well fail — but in an essential way, that’s a good thing. Why that’s the case is explained in an indispensable essay posted by media-technology thinker Clay Shirky a few days ago. Glancing as far back as the 16th-century advent of the printing press, Shirky’s piece is an illuminating synthesis of the industry’s past and present — and, from where I’m sitting, brims with aphoristic insights pointing to a bright future for digital journalism. Original reporting in that realm — still much underdeveloped and ripe for innovation, in my view — will play a vital role in the further transformation.

Shirky writes: “People committed to saving newspapers [keep] demanding to know ‘If the old model is broken, what will work in its place?’ To which the answer is: Nothing. Nothing will work. There is no general model for newspapers to replace the one the internet just broke.”

To the old journalism guard, that’s a heartbreaking epilogue. Which of course misses the point. (Revolutions create a curious inversion of perception, Shirky notes.) “With the old economics destroyed, organizational forms perfected for industrial production have to be replaced with structures optimized for digital data,” he continues. “It makes increasingly less sense even to talk about a publishing industry, because the core problem publishing solves — the incredible difficulty, complexity, and expense of making something available to the public — has stopped being a problem.”

Revolution is a dramatic word, but it’s exactly what we’re witnessing, if in slow motion. It began a little more than a decade ago and perhaps will require another decade before reaching a level of maturity and stability with new form. Shirky describes the familiar process: “The old stuff gets broken faster than the new stuff is put in its place. The importance of any given experiment isn’t apparent at the moment it appears; big changes stall, small changes spread. Even the revolutionaries can’t predict what will happen.”

(On recognizing “the importance of any given experiment,” see Shirky’s great distillation of the rise of Craigslist. Experiments are only revealed in retrospect to be turning points, he observes. And regarding “big changes stall” — the fashionable HuffPo model, anyone? With all due respect and admiration for its achievements during an epic election year, who really believes HuffPo’s almost-zero-reporting approach is the future of journalism?)

On with the greater experimentation and innovation, then. Many new attempts like The P-I probably will fail, and, in effect, we need them too. “There is one possible answer,” Shirky says, “to the question ‘If the old model is broken, what will work in its place?’ The answer is: Nothing will work, but everything might.”

About that big Jim Cramer beatdown

Jon Stewart is getting showered with praise for his showdown with CNBC’s Jim Cramer Thursday night on “The Daily Show.” The culmination of a week-long “feud” (egged on by the salivating media at large) was riveting to watch. (The video is here.) Stewart, long a savvy media critic, brutalized Cramer both for his own and the financial news network’s direct role in the economic meltdown that has vaporized untold wealth and hobbled the United States of America.

If that sounds a tad overdone, well, indeed. There is plenty of truthiness in Stewart’s point. It’s easy to sift through footage from various CNBC shows and find no shortage of their hosts making wrong calls about the financial markets, cheering on suspect CEOs and exuding what in hindsight was obviously misguided optimism about the economy and the stock market. Not to mention analyst Rick Santelli’s puerile, faux-populist tirade last month about the mortgage crisis.

But there is also some intellectual dishonesty suffusing the big CNBC takedown so in vogue right now. It’s easy to level simplistic snark at the network per above. But few seem willing, Stewart included, to acknowledge what the popular financial news network is mostly about, as I wrote about here recently: daily infotainment, emphasis on tainment.

Let’s be honest, we’re all plenty hungry at present for the villains of Wall Street to be strung up in the town square. But blame-the-media is the easy way out. It’s a bit silly to assign the degree of culpability that Stewart just did to a guy who, on his daily stock picking show, bounces around detonating obnoxious sound effects and exclaiming “Booyah!” like a frat guy on meth.

Stewart has other smart thinkers in the media following right along. David Brancaccio, host and senior editor of “Now on PBS,” told CNN that Thursday night’s show marked an important moment in journalism, especially for financial reporting, and that it may serve as a cautionary tale for those in the media who would fail on due diligence. “I don’t think any financial journalist wants to be in Cramer’s position,” Brancaccio said. “I think [journalists] may redouble their efforts to be dispassionate reporters asking the tough questions.”

That’s just goofy. Jim Cramer is not a financial journalist. He’s a self-cultivated nut-job host of a popular sideshow for Wall Street wonks. His script brims with speculative investment ideas, clumsy jokes and useless if marginally entertaining financial prattle.

The truth of the matter is that while CNBC certainly is ripe to take some lumps in this new era of Great Recession, the network is the easiest of targets. It’s also worth noting that there is substantive reporting in its mix. Last month, in fact, I spent some time interviewing CNBC anchor Maria Bartiromo and correspondent Bob Pisani at the New York Stock Exchange for a forthcoming magazine article about the financial media. Mostly I found them to be informed, thoughtful and dedicated to their work as reporters. For one example, see the high marks Bartiromo got for grilling ex-Merrill Lynch CEO John Thain on her show back in January. For another, watch this recent Frontline documentary, which recounts how in spring 2008 CNBC reporter David Faber helped pull the curtain back on Bear Stearns and impacted the timing of the investment bank’s collapse.

No doubt they and others on the network also had craven moments of their own during the boom times. As did so many in American government, business and, yes, out there in TV-viewing land. A dramatic and bloody round of the blame game is quite satisfying to watch right now, especially in the able hands of Mr. Stewart, but the culpability for our economic predicament extends far, far beyond the spectacle of one television channel.

This just in: No newspaper at all

More American newspapers appear to be accelerating toward demise. For anyone who’s been paying attention to the industry, it’s been clear at least since last fall that 2009 would be a year of considerable destruction. Take the spreading flame of digital technology, pour on a vicious economic downturn and quickly you have a raging forest fire. In the New York Times today Richard Pérez-Peña reports on which U.S. cities soon might not have a major daily print paper at all. Perhaps it’ll be Seattle or Denver. Or maybe San Francisco. Just a short while ago the prospect would’ve been inconceivable.

I like the forest fire metaphor here because it suggests an essential part of the picture that in many quarters still isn’t getting its proper due: The fertile rebirth that follows the destruction. I’ve been surprised to see a degree of pessimism even from some who’ve already been toiling on the frontier:

“It would be a terrible thing for any city for the dominant paper to go under, because that’s who does the bulk of the serious reporting,” says Joel Kramer, the editor and CEO of Minneapolis-based MinnPost.com, in the Times today. (Kramer was formerly editor and publisher of The Star Tribune.) “Places like us would spring up, but they wouldn’t be nearly as big. We can tweak the papers and compete with them, but we can’t replace them.”

“It would be a terrible thing for any city for the dominant paper to go under, because that’s who does the bulk of the serious reporting,” says Joel Kramer, the editor and CEO of Minneapolis-based MinnPost.com, in the Times today. (Kramer was formerly editor and publisher of The Star Tribune.) “Places like us would spring up, but they wouldn’t be nearly as big. We can tweak the papers and compete with them, but we can’t replace them.”

Really? There’s a tendency to equate the withering of the old medium (newsprint) with the demise of what it has delivered (news reporting). But increasingly it’s going to be delivered digitally. If the old media companies don’t do it, others will, because the demand (and therefore market) for it is undeniable. Sooner than we probably realize, we’re all going to be walking around carrying some kind of digital newspaper in our hands. Organizations will arise and mobilize to provide the reporting in it. And people will pay for it. (Businesses are also likely to advertise around it.)

Indeed, formidable challenges remain to working out viable business models. But the field is increasingly wide open and waiting to be seeded. (New tracts soon available!—see above.) You can look at the crisis as a tragedy, or you can look at it as an opportunity.

As Pérez-Peña notes, the Washington Post had a newsroom of more than 900 people six years ago, with fewer than 700 now. The LA Times newsroom is half the size it was in the 1990s, with a staff of about 600 today.

Call me crazy, but that’s still an awful lot of resources with which to gather and produce stories. Without the major printing and distribution costs of their antique brethren, digital ventures still will probably need to be considerably smaller and more nimble to succeed. (In the near-term economy, at least.) Even if some early experiments haven’t been so impressive, my sense is that those who survive and thrive will do so especially via robust local and regional reporting, fast dwindling in many places now. (Apparently the LA Times has some other strategy in mind.)

Self-described “newsosaur” Alan Mutter offers some intriguing advice for those who reportedly may launch the first digital-only newspaper in a major U.S. city, from the ashes of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. “Be different” and “cop an attitude,” he suggests. “Think of the site as more of a blog than a newspaper.”

Hmm, it seems there’s no shortage of that to go around… but I like his closing thoughts: “The work you do will play a major role in helping to define the future – and the future economics – of local news coverage. Take risks, try everything and have fun. Whatever you do, don’t look back.”

Mexico’s chilling drug war, at the door

In yesterday’s post about the chronically failing war on drugs, I didn’t mention Mexico — drug war-related problems just across the southern U.S. border have gotten big enough and scary enough to command their own focus. Mexico’s growing instability draws from a complex and long-running set of government and societal issues. But U.S. policy is a large and indisputable factor, and not just anti-drug policy. Indeed, our vast market for marijuana, cocaine and other illicit substances provides the criminal gangs with an endless river of cash. But even more troubling, our lax gun laws and prolific gun dealers supply them with stockpiles of nasty, sophisticated weaponry.

The contents of a new travel warning from the U.S. State Department posted in late February are nothing short of astonishing. The greatest increase in violence has occurred near the U.S. border. And it literally is a war:

Some recent Mexican army and police confrontations with drug cartels have resembled small-unit combat, with cartels employing automatic weapons and grenades. Large firefights have taken place in many towns and cities across Mexico but most recently in northern Mexico, including Tijuana, Chihuahua City and Ciudad Juarez.

The carnage, according to the State Department, has included “public shootouts during daylight hours in shopping centers and other public venues.” In Ciudad Juarez alone, just across the border from El Paso, Texas, Mexican authorities report that more than 1,800 people have been killed since January 2008.

Hot zones in Mexico's drug war. (Source: Wikimedia commons.)

According to a report in early March from “60 Minutes,” nearly 6,300 people were killed across Mexico last year in drug-related violence, double the amount of the prior year. There have been mass executions of policemen, kidnappings and beheadings. Mexico’s attorney general Eduardo Medina-Mora tells of weapons seizures including thousands of grenades, assault rifles and 50-caliber sniper rifles. The vast majority of them, he says, were acquired inside the United States.

Breaking the addiction to the drug war

In Vienna this Wednesday policy makers will convene once again to consider the United Nations strategy for battling illegal narcotics worldwide. It’s a war that is statistically impossible to win. A report today from the Guardian points to the massive cocaine trade out of Latin America to exemplify how the supply-side war on drugs is equivalent to shoveling water on an international scale:

The crucible is Colombia, the world’s main cocaine exporter. Since 2000 it has received $6 billion in mostly military aid from the US for the drug war. But despite the fumigation of 1.15m hectares of coca, the plant from which the drug is derived, production has not fallen. Across the whole of South America it has spiked 16%, thanks to increases in supply from Bolivia and Peru.

Says César Gaviria, Colombia’s former president and co-chair of the Latin American Commission on Drugs and Democracy: “Prohibitionist policies based on eradication, interdiction and criminalisation have not yielded the expected results. We are today farther than ever from the goal of eradicating drugs.”

Says Colonel René Sanabria, head of Bolivia’s anti-narcotic police force: “The strategy of the US here, in Colombia and Peru was to attack the raw material and it has not worked.”

Halfway around the world it’s the same story with the heroin trade out of Afghanistan.

Halfway around the world it’s the same story with the heroin trade out of Afghanistan.

Respected U.S. economists and judges agree: Our long-running drug policy with ideological roots tracing to Reagan and Nixon has gotten us nowhere.

If, as Tom Friedman argued yesterday, we have crossed a historic inflection point for fundamentally recasting our global economic paradigm, then it seems the costly war on drugs should be of a piece. There are no easy solutions, but there are promising alternatives to the status quo. A few years ago I reported an in-depth series for Salon examining “harm reduction” policy implemented in Vancouver, whose emphasis at a local level was on curbing drug demand and its attendant social problems. It appeared to work remarkably well.

There are signs the Obama administration might take things in a different direction. For his new director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy, President Obama reportedly has nominated Seattle police chief Gil Kerlikowske, whose views on drug policy seem decidedly more moderate than those of Bush-appointed hardliner John P. Walters. As the Guardian also notes today, a report last fall by the Government Accountability Office concluded the war on drugs had failed in Colombia — a report that was commissioned by then Senator Joe Biden.

Comments (4)

Comments (4)

You must be logged in to post a comment.