Archive for the ‘DFW’ Tag

Into the mind of David Foster Wallace

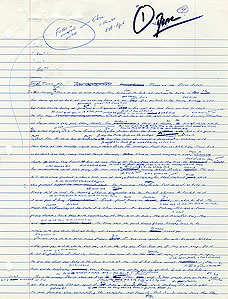

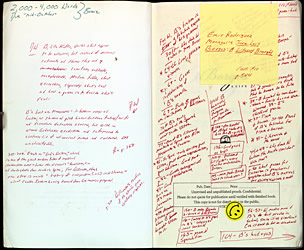

A few years back when I was working on craft at USF, I found inspiration in the idea that writers work in perpetual dialogue with their fellow scribes — not just immediate peers, but also those across geography and time. The books whose authors spoke to you — the ones that you kept returning to and sat with and spoke back to — granted insight and spurred productivity as much as any workshopping of manuscripts ever did. That kind of literary communion was something David Foster Wallace knew well. The archive at UT has already put some of his on display, with this look inside some of DFW’s intricately annotated books. (Click on the images at the above link to zoom in.) Inside his copy of The Puttermesser Papers, for example, you can see his studied list of Cynthia Ozick’s diction, from “telluric” to “pullulating” to “fructuous.” Notes scrawled inside the cover of Don Delillo’s Players reveal traces of his thinking about The Pale King, a novel he had yet to complete at his death: “Guy hired as lawyer for IRS. Sent to Peoria, but no one ever complains or contests audits in Peoria.”

Even just visually, as his copy of “Borges: A Life” shows, it’s easy to see that DFW’s immersions went deep:

There’s also a poignancy to seeing these snatches of handwritten script, an intimate reminder of his tragic, early exit. May the scholars soon get to work at UT and take us even deeper into the mind and methods of one of the great writers of his generation.

UPDATE: Lots more on the contents of the DFW archive from the New Yorker’s Book Bench blog.

Roger Federer’s impossible shot

The dazzling play of tennis titan Roger Federer does not cease to amaze. Following his U.S. Open semifinal victory on Sunday against Novak Djokovic, Federer said in a TV interview that he had practiced the between-the-legs return many times, but that “it never worked.” In case you missed what he called “the greatest shot I ever hit in my life” — that’s a bit like Michael Jordan trying to point out his single greatest dunk — take a look:

It must be noted that Djokovic himself played rather phenomenally, and likely would’ve vanquished just about any other opponent in the hard-fought three sets.

But when Federer is on, he seems to reach a truly singular plane of performance. David Foster Wallace captured it artfully in his 2006 essay, “Federer as Religious Experience.” (Which I wrote about here recently.) After stating that a top athlete’s beauty is “impossible to describe directly” or “to evoke,” DFW did just that, in one of his most memorable pieces of nonfiction. With Federer on the cusp of his sixteenth career Grand Slam title, it’s worth (re)reading the essay in its entirety. One line that has always stuck with me: “Federer’s forehand is a great liquid whip.” It’ll likely be on cracking display again in a couple of hours at Arthur Ashe Stadium, as he takes on 20-year-old Juan Martin del Potro of Argentina in the championship match.

UPDATE: Indeed, Federer hit no shortage of zingers in the five-set battle, but his serving fell short while the youthful (and towering, at 6-foot-6) del Potro dug deep to pull off one of the bigger upsets in U.S. Open history.

A Supposedly Fun Thing That Seems to Kill Whales

I took notice back when David Foster Wallace chronicled the cultural dark side of going on a cruise. But ultimately it’s the environmental dark side of the industry that makes me know I’ll Never Do It at All.

Over the weekend, an adult fin whale — a threatened species in Canada — turned up dead in the waters at a cruise ship terminal in Vancouver. The rare marine giant was impaled on the bow of the “Sapphire Princess,” a Princess Cruises’ ship arriving from Alaska:

(Jenelle Schneider/Vancouver Sun)

Tragic, gruesome and strange — the size of the ship really begins to sink in when you realize that the dead fin whale pictured above is approximately 70 feet long, a magnificent giant cruelly rendered small. (More photos here in the Vancouver Sun’s report, and more here on Flickr.) Consider, also, that soon the 2,670-passenger Sapphire Princess won’t even nearly measure up to the largest, most consumptive recreational beast riding the seas. That’ll be the stupefying Oasis of the Seas.

According to the Vancouver Sun, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans will conduct a necropsy to determine if the ship struck the fin whale while it was alive or if the whale had already been floating dead at sea and got caught on the bow. The latter seems the less likely scenario. A fisheries spokesperson, Lisa Spaven, appeared to acknowledge as much: “Vessel strikes are a very real threat to fin whales,” she told the Sun.

Moreover, an account I heard today from a source in Vancouver appears to contradict a statement put out by Princess Cruises this weekend regarding whales in the vicinity of the ship.

“It is unknown how or when this could have happened, as we have strict whale avoidance procedures in place when our ships are in the vicinity of marine life,” the statement from the cruise company said. “We are not aware that any whales were sighted as the ship sailed through the Inside Passage to Vancouver yesterday.”

But according to my source, two passengers who arrived on the Sapphire Princess in Vancouver this weekend said that several passengers on the ship had seen whales swimming around and under the ship as it traveled the Inside Passage cruise route just north of Vancouver Island.

Spaven, the DFO spokesperson, told the Vancouver Sun that she believes the whale was struck north of Vancouver Island, since fin whales aren’t normally found in the straits closer to Vancouver.

The Inside Passage is famously rich with marine wildlife and is a crucial habitat and migratory route for whales. As the Sun also reports: “This is the second time in the last 10 years that a cruise vessel has come into the Port of Vancouver with a whale caught on the bow. In that instance, in June of 1999, the Celebrity Cruise vessel MV Galaxy collided with an adult male fin whale, which likely happened as the ship transited the Hecate Strait north of Vancouver Island.”

For some compelling related reading, I strongly recommend Charles Siebert’s article “Watching Whales Watching Us,” published recently in the New York Times Magazine. It’s a deep, enthralling account that dives into some provocative thinking among marine biologists today about our evolving relationship with whales — which may yet hold hope, despite our terrible history of assault on one of the earth’s most sublime creatures.

PART 2:

There is more to Princess Cruises’ history with whales. In the summer of 2001, one of its ships slammed into a pregnant female humpback whale in the waters off Southeast Alaska, killing it. As Mother Jones reported two years ago via a National Park Service report, in January 2007 “Princess Cruise Lines pled guilty in U.S. District Court in Anchorage to a charge of knowingly failing to operate its vessel, the Dawn Princess, at a slow, safe speed in the summer of 2001 while near two humpback whales in the area of Glacier Bay National Park. The bloated carcass of a pregnant whale was found four days after the Princess ship sailed through the park. It had died of massive blunt trauma injuries to the right side of the head, including a fractured skull, eye socket and cervical vertebrae, all consistent with a vessel collision.”

You can read the rest of the report at the MoJo link above, including details of the six-figure penalty paid by Princess in a plea agreement. At the time of the agreement, the U.S. attorney’s office stated, “in this case we feel Princess has stepped up and made significant, voluntary operational changes that protect whales and the marine environment.”

Pending findings on the Sapphire Princess and the fin whale’s death, perhaps that assessment needs updating.

I’m compelled to add that I feel a particularly personal sense of investment in this story. Exactly a decade ago, I was fortunate to have an opportunity to travel into Glacier Bay, along with three good friends, on a 10-day sea kayaking trip. I’ve explored deep wilderness throughout my life, and Glacier Bay was among the most memorable places I’ve ever been. On a couple of days during the trip, we spotted cruise ships on the horizon. We were thankful to be far away from them. In this photo I took from my sea kayak in July 1999, you can see a large cruise ship in the distance (at the right-center edge of the image) heading north against the backdrop of the Fairweather Range.

We camped on nearby shoreline that night, where an exquisite sunset perhaps hinted at what was to come on day nine of our trip.

The next morning we paddled into the placid waters of Beartrack Cove to the east. We were sole representatives of humanity in a place that sees little of it. There were colorful marine birds, salmon returning to spawn in coastal streams… and suddenly that morning, one enormous humpback whale. It surfaced about 30 yards in front of our tiny, tiny boats.

The whale appeared to be feeding, its dark mass breaking the surface several times with its huge mouth open. We stopped paddling and tapped the rails of our boats gently to let it know our location. We watched in awe as it reappeared around us at various spots in the cove for about half an hour before it submerged for other waters.

It was the most glorious kind of nervous I think I’ve ever felt, a truly unforgettable experience.

A Titanic for these times

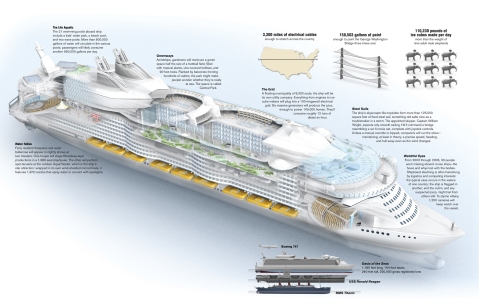

The June issue of the Atlantic has a look at the mind-blowing Oasis of the Seas, a gargantuan ocean liner forthcoming from cruise company Royal Caribbean International. Its unprecedented scale of apparent luxury surely required feats of engineering. But any awe that inspires would seem to wash away with apprehension of the ship’s untold economic and ecological hubris.

A decade ago, a large cruise ship typically carried in the neighborhood of 2,000 passengers and 1,000 crew members. But in an industry intently focused on swelling its profits no matter the non-fiscal costs, bigger is always better. Ordered in 2006 for $1.4 billion (on the crest ahead of the economic meltdown), the Oasis leaves those old numbers far in its wake. “In November,” writes Rory Nugent, “Royal Caribbean will take delivery of a true sea monster. Now in its final phase of construction, the Oasis of the Seas will be the biggest (longest, tallest, widest, heaviest) passenger ship ever built — and the most expensive. It will dwarf Nimitz-class aircraft carriers and cast shadows dockside atop 20-story buildings. A crew of 2,165 will tend the expectations of up to 6,296 passengers.” (Photos from the official Oasis site.)

According to the Atlantic, the ship has 21 swimming pools onboard, circulating more than 600,000 gallons of water. Passengers are expected to consume another 560,000 gallons per day, including daily production of 110,230 pounds of ice cubes — more than the weight of nine adult male elephants. The Oasis will also function as “its own utility company” with a 100-megawatt electrical grid — which will consume 12 tons of diesel fuel per hour and generate enough juice to power 105,000 homes.

There is a 1,380-seat playhouse onboard, though it’s not even the main attraction. That would be the outdoor “AquaTheater,” which apparently is “wrapped in its own wind-shielded microclimate” and uses nearly 2,000 nozzles to spray water in concert with a Las Vegas-style light show.

A good many people enjoy this kind of thing, the decadent vacation cruise. (Enough of them to support an industry with annual revenues in the tens of billions of dollars.) Based on the intuition that the experience might feel a bit like feasting on a nine-course meal in the middle of an Ethiopian refugee camp, I’ve never had any intention of trying it. David Foster Wallace famously once did. It’s a safe bet that the Oasis of the Seas would have left him royally retching. (His great essay “A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again,” originally published in Harper’s in 1996 as “Shipping Out,” was made available online by the magazine after his tragic death last fall.)

From Florida to Alaska, the consumptive ships of Royal Caribbean have been in the news before. Seven years ago federal investigators determined that the cruise company had covered up massive environmental malfeasance, despite a case focusing on one of its ships, the Norway, that resolved with a $1 million slap on the wrist. As USA Today reported in November 2002:

Now, some of the federal agents who investigated the case say the company’s pollution went on for much longer and was much worse than the light fine suggests. Environmental Protection Agency agents say — and court records support — that the Norway not only poured hundreds of thousands of gallons of oily bilge water into the ocean. It also dumped raw sewage mixed with hazardous, even cancer-causing, chemicals from dry cleaning and photo development into the waters near Miami for many years.

In the late 1990s, according to that USA Today report, Royal Caribbean had eventually pleaded guilty to 30 criminal charges in Miami, New York, Puerto Rico, Los Angeles, the Virgin Islands and Alaska, and had paid $27 million in fines in 1998 and ’99. By the 2002 news report, it had “implemented a companywide environmental compliance program.”

About to embark with its new mega-ship (click on the first link in this post to zoom in on the above graphic), has it since cleaned up its act? A year ago this week, a Royal Caribbean cruise ship dumped 20,000 gallons of contaminated water just off the coast of Southeast Alaska.

This is David Foster Wallace

On Tuesday, Little, Brown and Company publishes a book version of “This Is Water: Some Thoughts, Delivered on a Significant Occasion, about Living a Compassionate Life,” the celebrated commencement speech David Foster Wallace gave to the 2005 graduating class at Kenyon College. The pocket-sized book breaks up the nearly 4,000-word speech into digestible pieces on the page, some as brief as a single phrase. It’s an intriguing approach: In one sense, practical to publishing the essay in book form while drawing out its epigrammatic layers. At the same time, it seems rather un-DFW — contrary to the hyper-digressive, cascading prose for which he is so well-known.

Wallace giving a reading in 2006 in San Francisco. (Wikimedia Commons.)

Whether Wallace would approve of the presentation we probably can’t know. But it highlights a radiant directness that was often in danger of obscuring beneath his towering intellect. (It’s worth noting that there are some subtle differences to be found in other versions of the commencement speech floating out there; I contacted the publisher seeking clarification on how the text was prepared, but a publicist responded that Wallace’s longtime editor, Michael Pietsch, was declining to be interviewed about the book.)

Wallace’s focus was on the far from easy task of living life consciously in the adult world. He begins with a “didactic little parable-ish story,” as he puts it, about young fish who are oblivious to the environs through which they swim. More than just challenging the conventions of the commencement genre, Wallace makes use of them with a fierce sincerity: “I submit that this is what the real, no-bullshit value of your liberal arts education is supposed to be about: How to keep from going through your comfortable, prosperous, respectable adult life dead, unconscious, a slave to your head and to your natural default setting of being uniquely, completely, imperially alone, day in and day out.”

Segments like these carry an added poignancy in the wake of Wallace’s death by suicide last fall at the age of 46. Rather than a matter of morality or religion or the afterlife, he went on to tell the young graduates, “the capital-T Truth is about life before death. It is about making it to thirty, or maybe even fifty, without wanting to shoot yourself in the head.”

More striking, though, is his evocative insight and humor. If the students really do learn how to think and pay attention in life, he tells them, “It will actually be within your power to experience a crowded, hot, slow, consumer-hell-type situation as not only meaningful, but sacred, on fire with the same force that made the stars — compassion, love, the subsurface unity of all things. Not that that mystical stuff’s necessarily true: The only thing that’s capital-T True is that you get to decide how you’re going to try to see it.”

The pleasure of experiencing Wallace’s speech again underscored a realization I had when reading D.T. Max’s lengthy look back at Wallace’s life: The world deserves a published collection of David Foster Wallace’s correspondences, too. Various bits of it appearing in the recent New Yorker article — with fellow writer Jonathan Franzen, his literary agent Bonnie Nadell and others — cast additional light on Wallace’s humanity and highly emotive lexicon.

While I’ve admired some of his fiction, I’ve always thought Wallace was at his best with essays and literary journalism; as I wrote about here recently, gems found in his private correspondences show how the epistolary form (actual letters as well as email) brought out a more direct spirit of his, too.

The back cover of “This Is Water” asserts that the essay was Wallace’s answer to “the challenge of collecting all he believed about life and lasting fulfillment into a brief talk.” The inflated language of marketing copy, it would seem — Wallace’s prolific, restive consciousness probably could never be so perfectly distilled. A deeper look at his personal correspondences, meanwhile, could only add to the picture of a life and work tragically cut short and revered by so many.

Light in the darkness of David Foster Wallace

A prodigious amount has been written about David Foster Wallace since the heart-rending news of his suicide last September. The outpouring continues. This week, a humorous essay that keyed off Wallace’s hyper-baroque writing has seen a viral revival on the Web. Earlier this month, the New Yorker published a lengthy epilogue along with an excerpt from Wallace’s unfinished novel, “The Pale King.” His much-admired speech to the 2005 graduating class at Kenyon College in Ohio will come out in book form in April.

I finally had time to read the long New Yorker piece, and it made me realize that the world also deserves a published collection of Wallace’s correspondence, with fellow writer Jonathan Franzen, his literary agent Bonnie Nadell and others. The varied bits of it appearing in the New Yorker cast additional light on his humanity and highly emotive lexicon.

Steve Liss/Getty/Time Life

There is much insight and lyricism to be found in Wallace’s fiction, but it can be hard to track down and enjoy amid all the dense, cerebral text. He played language not as an instrument but as a postmodern orchestra, and it could get too cacophonous. (I remember when Bob Watts gave me his hardcover copy of “Oblivion,” barely cracked into. “Couldn’t really do it,” he said.) Although I much admired some of Wallace’s earlier short stories, I’ve always thought that he was at his best with essays and literary journalism. It seems the epistolary form (actual letters as well as email) brought out a more direct spirit of his, too, however painful. While in a deep rut in May 1990 he wrote to Franzen:

Right now, I am a pathetic and very confused young man, a failed writer at 28 who is so jealous, so sickly searingly envious of you and [William] Vollmann and Mark Leyner and even David fuckwad Leavitt and any young man who is right now producing pages with which he can live, and even approving them off some base clause of conviction about the enterprise’s meaning and end.

There was also a vivid kind of humor: In another correspondence with Franzen about 15 years later, this time regarding his struggles with “The Pale King,” Wallace wrote, “The whole thing is a tornado that won’t hold still long enough for me to see what’s useful and what isn’t … I’ve brooded and brooded about all this till my brooder is sore.”

One of his former editors recalls Wallace also comparing the writing of the novel with “trying to carry a sheet of plywood in a windstorm.”

For me, one of Wallace’s most memorable essays was published in August 2006 in the magazine Play, in which he profiled tennis titan Roger Federer.

A top athlete’s beauty is next to impossible to describe directly. Or to evoke. Federer’s forehand is a great liquid whip, his backhand a one-hander that he can drive flat, load with topspin, or slice — the slice with such snap that the ball turns shapes in the air and skids on the grass to maybe ankle height. His serve has world-class pace and a degree of placement and variety no one else comes close to; the service motion is lithe and uneccentric, distinctive (on TV) only in a certain eel-like all-body snap at the moment of impact. His anticipation and court sense are otherworldly, and his footwork is the best in the game — as a child, he was also a soccer prodigy. All this is true, and yet none of it really explains anything or evokes the experience of watching this man play. Of witnessing, firsthand, the beauty and genius of his game. You more have to come at the aesthetic stuff obliquely, to talk around it, or — as Aquinas did with his own ineffable subject — to try to define it in terms of what it is not.

It remains a memorable passage because it illumes not only Wallace’s profound talent, but also, in some sense, the linguistic-spiritual puzzle he died still trying to solve. He tells you it can’t be done and then he nearly does it, brilliantly. A deeper look at his personal correspondences — when presumably he was writing more free of the crushing performance pressures he put on himself — could only add to the picture.

Leave a comment

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.