The revolution will be further digitized

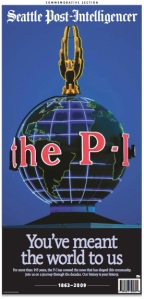

A large newspaper in a major American city has just gone all-digital. Depending on how you choose to look at it, the occasion is either tragic or revolutionary.

The 146-year-old Seattle Post-Intelligencer printed its last edition on Tuesday, becoming an Internet-only news source. In a report on its own Web site, the “paper” described the contours of the new, much smaller operation now in place. The P-I, as it’s called, is a “community platform” that will feature “breaking news, columns from prominent Seattle residents, community databases, photo galleries, 150 citizen bloggers and links to other journalistic outlets.” The New York Times notes that The P-I “will resemble a local Huffington Post more than a traditional newspaper,” with a news staff of about 20 people rather than the 165 it had, and with an emphasis more on commentary, advice and links to other sites than on original reporting.

The 146-year-old Seattle Post-Intelligencer printed its last edition on Tuesday, becoming an Internet-only news source. In a report on its own Web site, the “paper” described the contours of the new, much smaller operation now in place. The P-I, as it’s called, is a “community platform” that will feature “breaking news, columns from prominent Seattle residents, community databases, photo galleries, 150 citizen bloggers and links to other journalistic outlets.” The New York Times notes that The P-I “will resemble a local Huffington Post more than a traditional newspaper,” with a news staff of about 20 people rather than the 165 it had, and with an emphasis more on commentary, advice and links to other sites than on original reporting.

The P-I venture may well fail — but in an essential way, that’s a good thing. Why that’s the case is explained in an indispensable essay posted by media-technology thinker Clay Shirky a few days ago. Glancing as far back as the 16th-century advent of the printing press, Shirky’s piece is an illuminating synthesis of the industry’s past and present — and, from where I’m sitting, brims with aphoristic insights pointing to a bright future for digital journalism. Original reporting in that realm — still much underdeveloped and ripe for innovation, in my view — will play a vital role in the further transformation.

Shirky writes: “People committed to saving newspapers [keep] demanding to know ‘If the old model is broken, what will work in its place?’ To which the answer is: Nothing. Nothing will work. There is no general model for newspapers to replace the one the internet just broke.”

To the old journalism guard, that’s a heartbreaking epilogue. Which of course misses the point. (Revolutions create a curious inversion of perception, Shirky notes.) “With the old economics destroyed, organizational forms perfected for industrial production have to be replaced with structures optimized for digital data,” he continues. “It makes increasingly less sense even to talk about a publishing industry, because the core problem publishing solves — the incredible difficulty, complexity, and expense of making something available to the public — has stopped being a problem.”

Revolution is a dramatic word, but it’s exactly what we’re witnessing, if in slow motion. It began a little more than a decade ago and perhaps will require another decade before reaching a level of maturity and stability with new form. Shirky describes the familiar process: “The old stuff gets broken faster than the new stuff is put in its place. The importance of any given experiment isn’t apparent at the moment it appears; big changes stall, small changes spread. Even the revolutionaries can’t predict what will happen.”

(On recognizing “the importance of any given experiment,” see Shirky’s great distillation of the rise of Craigslist. Experiments are only revealed in retrospect to be turning points, he observes. And regarding “big changes stall” — the fashionable HuffPo model, anyone? With all due respect and admiration for its achievements during an epic election year, who really believes HuffPo’s almost-zero-reporting approach is the future of journalism?)

On with the greater experimentation and innovation, then. Many new attempts like The P-I probably will fail, and, in effect, we need them too. “There is one possible answer,” Shirky says, “to the question ‘If the old model is broken, what will work in its place?’ The answer is: Nothing will work, but everything might.”

Sex commune and the city

Ah, San Francisco, you gotta love this town. And loving it must include acknowledging that from time to time certain of its, um, cultural stimulations can seem a bit absurd. This was on display yesterday in the Sunday Styles section of the New York Times, which reported on the One Taste Urban Retreat Center, a 38-member live-play arrangement housed in “a shabby-chic loft building” in the city’s South of Market district. Its men and women (their average age the late 20s, the Times says) make meals together, practice yoga and meditation, and run communication workshops for groups of visitors. Oh, and also:

At 7 a.m. each day, as the rest of America is eating Cheerios or trying to face gridlock without hyperventilating, about a dozen women, naked from the waist down, lie with eyes closed in a velvet-curtained room, while clothed men huddle over them, stroking them in a ritual known as orgasmic meditation — “OMing,” for short. The couples, who may or may not be romantically involved, call one another “research partners.”

Apparently there are benefits to this of all sorts. One recently divorced man, “a baby-faced 50-year-old Silicon Valley engineer,” told the Times that “the practice of manually fixing his attention on a tiny spot of a woman’s body improves his concentration at work.”

Past practices at the center, which has been operating for over four years, include naked yoga. Anyone who has ever participated in a public yoga class knows this would be a remarkably ill-advised idea, no matter the direction in which it might be stretched. One Taste reportedly discontinued it after word got around and “many voyeuristic non-yogis showed up.” (Ya don’t say.)

San Francisco and surrounds has a well-known heritage, of course, of communal sexual experimentation and spiritual seeking. As far as I know per the history books, combining the two has never led to any particularly enlightening results.

What I find intriguing about this story isn’t a matter of morals or taste — it’s that the language and marketing themes are age-old, and not newly convincing. One Taste’s web site says that “Orgasmic meditation is a technique that develops mindfulness, concentration, connectedness and insight in a paired practice that focuses on sensation generated through manual stimulation of the genitals.” The practice can “facilitate greater physical and mental health, deeper connection to relationship” and can even be “a method for spiritual aims.”

In the Times report, a once timid patron turned instructor speaks of “the lingering velocity of my desire and my hesitation to give into it.” The proprietor and leader, Nicole Daedone, admits “a high potential for this to be a cult.” And while the article notes toward the end that Daedone’s current boyfriend, a wealthy software entrepreneur, “makes financial resources available” in support of the business, curiously, one stone remains unturned: cash flow. One Taste’s own program listings are also conspicuously absent information about what its participants are required to pay.

About that big Jim Cramer beatdown

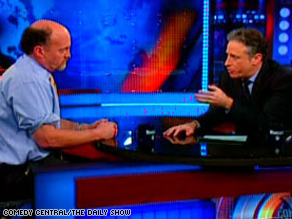

Jon Stewart is getting showered with praise for his showdown with CNBC’s Jim Cramer Thursday night on “The Daily Show.” The culmination of a week-long “feud” (egged on by the salivating media at large) was riveting to watch. (The video is here.) Stewart, long a savvy media critic, brutalized Cramer both for his own and the financial news network’s direct role in the economic meltdown that has vaporized untold wealth and hobbled the United States of America.

If that sounds a tad overdone, well, indeed. There is plenty of truthiness in Stewart’s point. It’s easy to sift through footage from various CNBC shows and find no shortage of their hosts making wrong calls about the financial markets, cheering on suspect CEOs and exuding what in hindsight was obviously misguided optimism about the economy and the stock market. Not to mention analyst Rick Santelli’s puerile, faux-populist tirade last month about the mortgage crisis.

But there is also some intellectual dishonesty suffusing the big CNBC takedown so in vogue right now. It’s easy to level simplistic snark at the network per above. But few seem willing, Stewart included, to acknowledge what the popular financial news network is mostly about, as I wrote about here recently: daily infotainment, emphasis on tainment.

Let’s be honest, we’re all plenty hungry at present for the villains of Wall Street to be strung up in the town square. But blame-the-media is the easy way out. It’s a bit silly to assign the degree of culpability that Stewart just did to a guy who, on his daily stock picking show, bounces around detonating obnoxious sound effects and exclaiming “Booyah!” like a frat guy on meth.

Stewart has other smart thinkers in the media following right along. David Brancaccio, host and senior editor of “Now on PBS,” told CNN that Thursday night’s show marked an important moment in journalism, especially for financial reporting, and that it may serve as a cautionary tale for those in the media who would fail on due diligence. “I don’t think any financial journalist wants to be in Cramer’s position,” Brancaccio said. “I think [journalists] may redouble their efforts to be dispassionate reporters asking the tough questions.”

That’s just goofy. Jim Cramer is not a financial journalist. He’s a self-cultivated nut-job host of a popular sideshow for Wall Street wonks. His script brims with speculative investment ideas, clumsy jokes and useless if marginally entertaining financial prattle.

The truth of the matter is that while CNBC certainly is ripe to take some lumps in this new era of Great Recession, the network is the easiest of targets. It’s also worth noting that there is substantive reporting in its mix. Last month, in fact, I spent some time interviewing CNBC anchor Maria Bartiromo and correspondent Bob Pisani at the New York Stock Exchange for a forthcoming magazine article about the financial media. Mostly I found them to be informed, thoughtful and dedicated to their work as reporters. For one example, see the high marks Bartiromo got for grilling ex-Merrill Lynch CEO John Thain on her show back in January. For another, watch this recent Frontline documentary, which recounts how in spring 2008 CNBC reporter David Faber helped pull the curtain back on Bear Stearns and impacted the timing of the investment bank’s collapse.

No doubt they and others on the network also had craven moments of their own during the boom times. As did so many in American government, business and, yes, out there in TV-viewing land. A dramatic and bloody round of the blame game is quite satisfying to watch right now, especially in the able hands of Mr. Stewart, but the culpability for our economic predicament extends far, far beyond the spectacle of one television channel.

This just in: No newspaper at all

More American newspapers appear to be accelerating toward demise. For anyone who’s been paying attention to the industry, it’s been clear at least since last fall that 2009 would be a year of considerable destruction. Take the spreading flame of digital technology, pour on a vicious economic downturn and quickly you have a raging forest fire. In the New York Times today Richard Pérez-Peña reports on which U.S. cities soon might not have a major daily print paper at all. Perhaps it’ll be Seattle or Denver. Or maybe San Francisco. Just a short while ago the prospect would’ve been inconceivable.

I like the forest fire metaphor here because it suggests an essential part of the picture that in many quarters still isn’t getting its proper due: The fertile rebirth that follows the destruction. I’ve been surprised to see a degree of pessimism even from some who’ve already been toiling on the frontier:

“It would be a terrible thing for any city for the dominant paper to go under, because that’s who does the bulk of the serious reporting,” says Joel Kramer, the editor and CEO of Minneapolis-based MinnPost.com, in the Times today. (Kramer was formerly editor and publisher of The Star Tribune.) “Places like us would spring up, but they wouldn’t be nearly as big. We can tweak the papers and compete with them, but we can’t replace them.”

“It would be a terrible thing for any city for the dominant paper to go under, because that’s who does the bulk of the serious reporting,” says Joel Kramer, the editor and CEO of Minneapolis-based MinnPost.com, in the Times today. (Kramer was formerly editor and publisher of The Star Tribune.) “Places like us would spring up, but they wouldn’t be nearly as big. We can tweak the papers and compete with them, but we can’t replace them.”

Really? There’s a tendency to equate the withering of the old medium (newsprint) with the demise of what it has delivered (news reporting). But increasingly it’s going to be delivered digitally. If the old media companies don’t do it, others will, because the demand (and therefore market) for it is undeniable. Sooner than we probably realize, we’re all going to be walking around carrying some kind of digital newspaper in our hands. Organizations will arise and mobilize to provide the reporting in it. And people will pay for it. (Businesses are also likely to advertise around it.)

Indeed, formidable challenges remain to working out viable business models. But the field is increasingly wide open and waiting to be seeded. (New tracts soon available!—see above.) You can look at the crisis as a tragedy, or you can look at it as an opportunity.

As Pérez-Peña notes, the Washington Post had a newsroom of more than 900 people six years ago, with fewer than 700 now. The LA Times newsroom is half the size it was in the 1990s, with a staff of about 600 today.

Call me crazy, but that’s still an awful lot of resources with which to gather and produce stories. Without the major printing and distribution costs of their antique brethren, digital ventures still will probably need to be considerably smaller and more nimble to succeed. (In the near-term economy, at least.) Even if some early experiments haven’t been so impressive, my sense is that those who survive and thrive will do so especially via robust local and regional reporting, fast dwindling in many places now. (Apparently the LA Times has some other strategy in mind.)

Self-described “newsosaur” Alan Mutter offers some intriguing advice for those who reportedly may launch the first digital-only newspaper in a major U.S. city, from the ashes of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. “Be different” and “cop an attitude,” he suggests. “Think of the site as more of a blog than a newspaper.”

Hmm, it seems there’s no shortage of that to go around… but I like his closing thoughts: “The work you do will play a major role in helping to define the future – and the future economics – of local news coverage. Take risks, try everything and have fun. Whatever you do, don’t look back.”

Precisely the poet we needed

Kay Ryan was in town for a reading on Friday night at the San Francisco Center for the Book. It was packed. It occurred to me it was absolutely right she’d become our U.S. Poet Laureate in a time of so much turmoil near and far. The universe has a way of balancing itself, even when it seems barely to be standing on one foot. Some comic concision to cut through all the gloomy cacophony—just the thing.

I’ve been an admirer for years of Ryan’s pithy assessments. They seem even more necessary right now, and not just for their luminous resuscitation of dead language and reanimation of cliché. As she put it on Friday, one of her interests has been considering extremity and trying to “cool things down” a bit. Claims found in “Ripley’s Believe it or Not!” became the source for her latest collection The Jam Jar Lifeboat & Other Novelties Exposed. The poem “Murder at Midnight” departs from Ripley’s assertion that “If everyone who was told about it told two other people within 12 minutes, everybody on earth would know about it before morning.” Determines Ryan:

I’ve been an admirer for years of Ryan’s pithy assessments. They seem even more necessary right now, and not just for their luminous resuscitation of dead language and reanimation of cliché. As she put it on Friday, one of her interests has been considering extremity and trying to “cool things down” a bit. Claims found in “Ripley’s Believe it or Not!” became the source for her latest collection The Jam Jar Lifeboat & Other Novelties Exposed. The poem “Murder at Midnight” departs from Ripley’s assertion that “If everyone who was told about it told two other people within 12 minutes, everybody on earth would know about it before morning.” Determines Ryan:

But people would begin getting it

a little bit wrong. Long before daylight,

the ‘murder at midnight’ would be

‘sugar stolen outright.’ The fate

of the dead man would not extend

beyond his gate. Only those

right now missing his little habits,

his footfall, his sleeping noises,

will know, and they can’t really tell;

news doesn’t really travel very well.

Whether Ripley’s math quite holds up under scrutiny I can’t say, but no matter. This morning a friend from a group of old high school buddies emailed to suggest that we all start using the trendy messaging service Twitter to banter and keep in touch on a more frequent basis. With three email accounts, IM, Facebook and a blog already running me apace on the digital information wheel, I’m thinking I’ll gently decline for now, and refer him to Sasha Cagen’s fine essay posted yesterday, This Is Your Brain on Twitter.

Mexico’s chilling drug war, at the door

In yesterday’s post about the chronically failing war on drugs, I didn’t mention Mexico — drug war-related problems just across the southern U.S. border have gotten big enough and scary enough to command their own focus. Mexico’s growing instability draws from a complex and long-running set of government and societal issues. But U.S. policy is a large and indisputable factor, and not just anti-drug policy. Indeed, our vast market for marijuana, cocaine and other illicit substances provides the criminal gangs with an endless river of cash. But even more troubling, our lax gun laws and prolific gun dealers supply them with stockpiles of nasty, sophisticated weaponry.

The contents of a new travel warning from the U.S. State Department posted in late February are nothing short of astonishing. The greatest increase in violence has occurred near the U.S. border. And it literally is a war:

Some recent Mexican army and police confrontations with drug cartels have resembled small-unit combat, with cartels employing automatic weapons and grenades. Large firefights have taken place in many towns and cities across Mexico but most recently in northern Mexico, including Tijuana, Chihuahua City and Ciudad Juarez.

The carnage, according to the State Department, has included “public shootouts during daylight hours in shopping centers and other public venues.” In Ciudad Juarez alone, just across the border from El Paso, Texas, Mexican authorities report that more than 1,800 people have been killed since January 2008.

Hot zones in Mexico's drug war. (Source: Wikimedia commons.)

According to a report in early March from “60 Minutes,” nearly 6,300 people were killed across Mexico last year in drug-related violence, double the amount of the prior year. There have been mass executions of policemen, kidnappings and beheadings. Mexico’s attorney general Eduardo Medina-Mora tells of weapons seizures including thousands of grenades, assault rifles and 50-caliber sniper rifles. The vast majority of them, he says, were acquired inside the United States.

Breaking the addiction to the drug war

In Vienna this Wednesday policy makers will convene once again to consider the United Nations strategy for battling illegal narcotics worldwide. It’s a war that is statistically impossible to win. A report today from the Guardian points to the massive cocaine trade out of Latin America to exemplify how the supply-side war on drugs is equivalent to shoveling water on an international scale:

The crucible is Colombia, the world’s main cocaine exporter. Since 2000 it has received $6 billion in mostly military aid from the US for the drug war. But despite the fumigation of 1.15m hectares of coca, the plant from which the drug is derived, production has not fallen. Across the whole of South America it has spiked 16%, thanks to increases in supply from Bolivia and Peru.

Says César Gaviria, Colombia’s former president and co-chair of the Latin American Commission on Drugs and Democracy: “Prohibitionist policies based on eradication, interdiction and criminalisation have not yielded the expected results. We are today farther than ever from the goal of eradicating drugs.”

Says Colonel René Sanabria, head of Bolivia’s anti-narcotic police force: “The strategy of the US here, in Colombia and Peru was to attack the raw material and it has not worked.”

Halfway around the world it’s the same story with the heroin trade out of Afghanistan.

Halfway around the world it’s the same story with the heroin trade out of Afghanistan.

Respected U.S. economists and judges agree: Our long-running drug policy with ideological roots tracing to Reagan and Nixon has gotten us nowhere.

If, as Tom Friedman argued yesterday, we have crossed a historic inflection point for fundamentally recasting our global economic paradigm, then it seems the costly war on drugs should be of a piece. There are no easy solutions, but there are promising alternatives to the status quo. A few years ago I reported an in-depth series for Salon examining “harm reduction” policy implemented in Vancouver, whose emphasis at a local level was on curbing drug demand and its attendant social problems. It appeared to work remarkably well.

There are signs the Obama administration might take things in a different direction. For his new director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy, President Obama reportedly has nominated Seattle police chief Gil Kerlikowske, whose views on drug policy seem decidedly more moderate than those of Bush-appointed hardliner John P. Walters. As the Guardian also notes today, a report last fall by the Government Accountability Office concluded the war on drugs had failed in Colombia — a report that was commissioned by then Senator Joe Biden.

Hard truths about the Iraq war

1. With such enormous problems at home, it is hard to focus on enormous problems beyond U.S. borders, even when we perceive the dangers of turning too inward.

2. It is hard not to be exhausted of and desensitized to the whole awful mess. A week from this Thursday, it will have been six years since George W. Bush launched “shock and awe.” For the vast majority of Americans who have no direct connection to the war, if we are brutally honest with ourselves, it is hard in some respects to care at this point. (More on this below.)

3. It is but one of two daunting wars we are fighting. (And the new president is poised to make the other one larger.)

4. It is far, far from over.

Despite items one and two above, distinguished military reporter Thomas Ricks had some tranfixing things to say about the war on Wednesday, during an interview on NPR about his new book. Ricks’ comments are likely to prove distinct from the White House talking points and news coverage that will mark the six-year anniversary of the conflict in the coming days. His reporting in Iraq, including interviews in 2008 with Ambassador Ryan Crocker, the top U.S. diplomat there, left Ricks to conclude, “The events for which this war will be remembered have not yet happened.” Here’s a bit more of what was most striking among his comments, from the forbidding magnitude of the problem to some startling attitudes about the war that Ricks encountered while promoting his book recently in the liberal-by-reputation Bay Area:

Despite items one and two above, distinguished military reporter Thomas Ricks had some tranfixing things to say about the war on Wednesday, during an interview on NPR about his new book. Ricks’ comments are likely to prove distinct from the White House talking points and news coverage that will mark the six-year anniversary of the conflict in the coming days. His reporting in Iraq, including interviews in 2008 with Ambassador Ryan Crocker, the top U.S. diplomat there, left Ricks to conclude, “The events for which this war will be remembered have not yet happened.” Here’s a bit more of what was most striking among his comments, from the forbidding magnitude of the problem to some startling attitudes about the war that Ricks encountered while promoting his book recently in the liberal-by-reputation Bay Area:

On the time frame we face:

“I think we may just be halfway through this war. I know President Obama thinks he’s going to get all troops out by the end of 2011. I don’t know anyone in Baghdad who thinks that’s going to happen. I think Iraq is going to change Obama more than Obama changes Iraq.”

On the scope of the disaster:

“The original U.S. war plan was to be down to 30,000 troops by September 2003…. I do think this war was the biggest mistake in the history of American foreign policy. I think it’s a tragedy. I think George Bush’s mistakes are something we’re going to be paying for for decades. We don’t yet understand how big a mistake this is.”

On the destructive prospects of the U.S. military pulling out:

“I think Americans are really sick of the Iraq war…. I was speaking in California last week, near liberal Mill Valley, and I said, Look, if you leave right now this could lead to genocide. And somebody in the audience said, ‘So what.’ And somebody else said, ‘Genocide happens all the time.’ And I thought, my god, Americans are willing to take genocide in Iraq, and just leave.”

Faces of the recession in San Francisco

I thought it would be illuminating to get past the abstract brutality of the reported figures, to match some real faces with the numbers. A short visit today to the California Employment Development Department on Turk Street provided about 40 of them.

“Unemployed Men sitting on the sunny side of the San Francisco Public Library” by Dorothea Lange. Feb. 1937. Courtesy of the San Francisco History Center.

At a “job focus workshop” for people collecting unemployment insurance, the EDD instructor directed the conversation around two crowded conference room tables. People of all kinds listed their occupational fields and spoke briefly about how their job search was going. Not at all well. A few remained upbeat, but the discouragement and resignation among many was palpable. To some degree it was a matter of the diverse Bay Area economy, but the breadth of the carnage was still astonishing. No age or job sector was immune.

There were as many mid to senior-level professionals as working class folks, if not more of them. David, a lawyer for an energy company. Linda, a commercial real estate broker. Michael, a manager from a biotech firm. Also present: several people in marketing and sales, two people in the printing business, two bank tellers, an accountant, a travel agent, a telecom maintenance worker, a warehouse manager, an ice cream delivery truck driver, a construction worker, a creative director for an advertising agency, an environmental consultant, a mental health worker and a professional photographer.

The health care industry is said to be one of the few bright spots right now in terms of prospects. But here, too, was Olga, a soft-spoken middle-age woman, recently laid off from her job at a nursing home. Next she tried to pick up work as a home-care provider, but that didn’t last either. Apparently people losing their jobs are also giving up on health insurance for themselves and their families.

“This week I’ve been going door to door at offices downtown, asking to see if they need a receptionist,” Olga said. “Nothing yet.”

Someone across the room let out a small sigh.

Recently, a friend of mine who works downtown noted that the buses headed there during morning rush hour have been noticeably less full. Some popular lunch spots have started to look sparse. On a recent afternoon she was in a sandwich shop when a Latino man walked in, approached the counter and simply began pleading in a broken accent.

“I need a job,” he said, “I need a job.”

The future of Internet news, circa 1981

This ancient clip from a local San Francisco broadcast has been floating around for a while, but it keeps popping up in discussions about the fate of the newspaper industry, so I couldn’t resist. It’s pretty priceless viewing if you haven’t seen it.

And not just because it’s hilariously antique — it’s also a prelude to a cautionary tale. Believe it or not, the San Francisco Examiner was once working on the cutting edge of the Internet. The Examiner’s David Cole certainly intended no irony when interviewed then about their “electronic newspaper” experiment: “We’re trying to figure out what it’s going to mean to us as editors and reporters and what it means to the home user. And we’re not in it to make money. We’re probably not going to lose a lot, but we aren’t going to make much, either.”

Online media pioneer Scott Rosenberg (at the Examiner himself back in the 1980s and a mentor of mine at Salon in the early 2000s) wrote insightfully about this clip a few weeks back, and how far the newspaper industry hasn’t come:

The spirit of experimentation that the Examiner set out with in 1981 dried up, replaced by an industry-wide allergy to fundamental change. “Let’s use the new technology,” editors and executives would say, “but let’s not let the technology change our profession or our industry.” They largely succeeded in resisting change. Now it’s catching up with them.

That’s probably putting it lightly, considering the current state of the San Francisco Chronicle (a participant in the 1981 “experiment”), the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, the Rocky Mountain News and so many others.

Today, a heartfelt eulogy from Nancy Mitchell, a former reporter for the freshly defunct Rocky, carries its own layer of irony. Mitchell’s sentiments are genuine and noble, and certainly appreciated by this fellow newspaper fan and ardent believer in the value of quality reporting.

But Mitchell falls yet into the trap described above — denial of inexorable industry transformation, and a failure of imagination. She blames faceless management types at the Rocky for attempting foolish or half-baked ways to recast the paper in a time of dramatic change. (No doubt they did.) She quietly denigrates experimentation with digital tools like blogs, Flickr and Twitter, as if nobody interested in serious journalism should have to deal with “the anxiety attached to learning the gimmicks.” She seeks shelter in a credo once posted in her managing editor’s office: “Three simple rules, not produced by a focus group: Get the news. Tell the truth. Don’t be dull. I’d like to believe we did all three.”

What Mitchell doesn’t seem to realize is that all three — and more — increasingly can and will be done digitally. The audience will be there to engage with it. Business models will arise to support it. Technology will keep transforming it. It seems obvious to say it’s the way the world is fast going, whether with reporting, commentary or many other information-based creations. Just note where her piece was published, of course, and how you’re encountering it right now.

Putting lipstick on a bear

The Dow Jones average is swimming down around 6,800 today, hitting a new 12-year low. If in a basic sense the stock market represents a rough overall valuation of the U.S. economy, then the U.S. economy is now worth less than it was in April of 1997. Whether that’s realistic I have no idea, but either way it seems a rather stunning measure.

In recent days, by way of working on a forthcoming magazine article, I’ve been taking in a sizable dose of CNBC, the ubiquitous financial news network. The channel is watched obsessively by most on Wall Street (I saw this firsthand on a recent reporting trip to the New York Stock Exchange and surrounds), and its constant chatter can be found in airport lounges, urban corner stores and no doubt the many living rooms of America’s investor class. The personalities hosting CNBC’s various shows do produce substantive reporting on the financial world daily, but much of the air time is filled with infotainment, emphasis on tainment. In addition to the usual stream of industry banter and speculative investing ideas, these days there’s no shortage of finger-pointing commentary about the policy maneuvers of the Obama administration.

Still, you can’t run a popular cable network on a steady drip of downer, so today the hosts of CNBC’s “Power Lunch” have been trying their darn best to dress up another ugly day on Wall Street. Courtesy of their “smart strategies special,” cue the segment: Three ways to make money in value stocks!

“Apparently there are more value stocks out there than ever,” announces Sue Herera, preparing to welcome two money managers who’ll offer favored picks.

“Value stocks are being created right now,” declares a smiling Bill Griffith, glancing sidelong at the sinking averages.

Good luck, folks. As James Grant noted in a sobering roundup of financial experts in yesterday’s Times, the truth about vicious bear markets is that they end when investors finally give up hope. “Hope sustains life,” Grant writes, “but misplaced hope prolongs recessions.”

A reality check for the recovery plan haters

It doesn’t seem particularly out of the ordinary when Rush Limbaugh looks at Obama’s economic recovery plan and reiterates his desire to see the president fail. Or when Gov. Bobby Jindal, purportedly the rising star of the Republican Party, argues that federal spending is a bad way to pull the nation back from the brink. But these are no ordinary times — faced with the greatest domestic crisis in modern memory, at what point does hard-line politics make for sheer lunacy?

While reporting for a forthcoming magazine piece, I spoke recently with economist Dean Baker about some of the political right’s machinations regarding the economic meltdown.

“One thing that was amazing to me was people blaming the housing crisis on the Community Reinvestment Act. It makes no sense whatsoever,” said Baker, who is co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research in Washington. “The idea was widely circulated, so there are a lot of people out there who believe that what lies at the center of the crisis is that the government forced banks to make loans to poor people and minorities. That’s absurd, and the media should’ve been doing more to point that out.”

A few did, at least: Businessweek’s Aaron Pressman explained last fall why the 1977 federal law, requiring banks to lend in low-income neighborhoods where they take deposits, had little to do with the insidious subprime mortgages that inflated the housing bubble. (Pressman further pointed out that the Bush government in fact weakened the CRA, while enabling Wall Street to gorge on dubious derivatives and absurd leverage.) But the blame game holds powerful emotional appeal in dark days, and the warriors of the right soldier on in earnest.  Fox News’ Sean Hannity keeps repeating a debunked GOP talking point that the freshly signed $787 billion recovery package contains a $30 million provision to save a salt marsh mouse in San Francisco. Simply erroneous, as Congressman Joe Sestak pointed out this week on Hannity’s own show. (Here’s the video.)

Fox News’ Sean Hannity keeps repeating a debunked GOP talking point that the freshly signed $787 billion recovery package contains a $30 million provision to save a salt marsh mouse in San Francisco. Simply erroneous, as Congressman Joe Sestak pointed out this week on Hannity’s own show. (Here’s the video.)

Baker worries that partisan warfare will squelch political appetite for additional stimulus — which he believes will be necessary going forward. Obama had to fight hard just to get the first big spending plan through Congress. “Nobody wants to waste money,” Baker said, pointing out that job creation and a particular project’s usefulness are different issues. “But if the alternative is that people think we’re somehow going to benefit by not spending money, then they’re just on another planet.” Without more government spending to come, he said, “we could see this downward spiral continue for some time.”

Comments (1)

Comments (1)

You must be logged in to post a comment.