Archive for the ‘foreign affairs’ Tag

Osama bin Laden’s “man-caused disaster”?

President Obama’s predecessor famously terrorized the English language. But lately, as the new, more fluent commander in chief and his team leave behind George W. Bush’s linguistic legacy on national security — jettisoning hard-line terminology such as “war on terrorism” and “enemy combatant” — they seem in danger of over-articulating.

In a recent interview with Der Spiegel, Janet Napolitano explained why, in her first testimony to Congress as Homeland Security chief, she used particular language to describe continuing perils. “In my speech, although I did not use the word ‘terrorism,’ I referred to ‘man-caused’ disasters,” she said. “That is perhaps only a nuance, but it demonstrates that we want to move away from the politics of fear toward a policy of being prepared for all risks that can occur.”

A worthy goal. But considering the mass casualties perpetrated in Manhattan or Madrid or London in recent years, is it really a good idea to deploy a phrase that’s in danger of suggesting accidental tragedy?

As Peter Baker reports in the New York Times, the Obama administration is opening itself to criticism that it doesn’t take the dangers of the world seriously enough. Says Shannen W. Coffin, who served as counsel to former Vice President Dick Cheney: “They seem more interested in the war on the English language than in what might be thought of as more pressing national security matters. An Orwellian euphemism or two will not change the fact that bad people want to kill us and destroy us as a free people.”

One can always count on a loaded partisan volley from the Cheney camp, but in this case one perhaps not easily deflected in the battle of political perception.

Another national security legacy of the Bush era, deeply troubling, lingers. An internal report from late 2008 assessing the state of the U.S. intelligence system, made public this week, found precious little progress since 9/11 in terms of fixing serious bureaucratic risks. That’s despite the greatest overhaul since World War II of the system, including the creation of the Office of the Director of National Intelligence to oversee America’s spy agencies.

Another national security legacy of the Bush era, deeply troubling, lingers. An internal report from late 2008 assessing the state of the U.S. intelligence system, made public this week, found precious little progress since 9/11 in terms of fixing serious bureaucratic risks. That’s despite the greatest overhaul since World War II of the system, including the creation of the Office of the Director of National Intelligence to oversee America’s spy agencies.

Many senior U.S. intelligence officials interviewed “were unable to articulate a clear understanding of the ODNI’s mission, roles, and responsibilities,” according to the report. U.S. spy agencies are still running “largely disconnected and incompatible” computer systems and have “no standard architecture supporting the storage and retrieval of sensitive intelligence.” And “intelligence information and reports are frequently not being disseminated in a timely manner.”

And while the concept of sharing information between agencies is “supported in principle” among some intelligence leaders, according to the report, “the culture of protecting ‘turf’ remains a problem, and there are few, if any, consequences for failure to collaborate.”

Hopefully the true consequences of such recent turf battles, and the excruciating story behind them, haven’t already gone forgotten.

Seeing Obama’s burden, the drug war and more

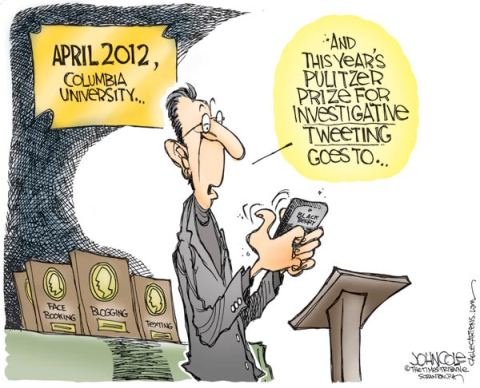

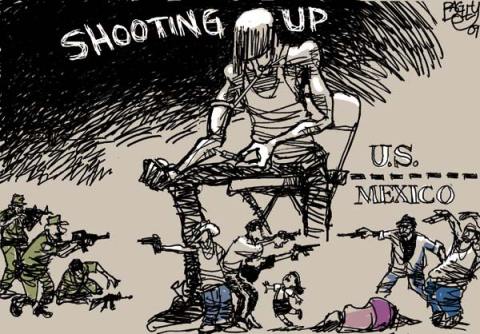

Even in the loquacious realm known as the blogosphere, it is possible at times to lack words. Or to feel that there are simply too many of them. Either way, Daryl Cagle’s Political Cartoonists Index offers a pleasing alternative. Here are three recent entries that caught my eye.

Hajo (Amsterdam), on President Obama’s economic travails:

John Cole (Scranton, PA), peering into journalism’s truncated future:

Pat Bagley (Salt Lake City), a potent take on the Mexican-American drug war:

Could marijuana light up the economy?

The debate about whether to legalize marijuana in the United States has never been a mainstream one. So it’s been fascinating to watch how much attention the concept has gotten lately, however viable it may or may not be.

Preoccupation with Mexico’s violent drug war is one factor; marijuana is the largest source of revenue for the cartels’ multibillion dollar business north of the border. Commodify the major cash crop through legalization, the idea goes, and its cost will plummet, putting a serious dent in the bad guys’ bank accounts.

But the larger issue lighting up the idea seems to be the battered American economy. In February, California state lawmaker Tom Ammiano proposed legislation that would regulate the cultivation and sale of marijuana, with a potential tax windfall of more than $1 billion to help bail out the state from a severe budget crisis.

But the larger issue lighting up the idea seems to be the battered American economy. In February, California state lawmaker Tom Ammiano proposed legislation that would regulate the cultivation and sale of marijuana, with a potential tax windfall of more than $1 billion to help bail out the state from a severe budget crisis.

On Thursday, the legalization concept wafted all the way up to the presidential level. In a live Internet “video chat” with Americans, President Obama found himself responding to a question that had been voted among the most popular of those submitted by the public: whether the controlled sale and taxation of marijuana could help stimulate the U.S. economy. “I don’t know what this says about the online audience,” Obama quipped. “The answer is no, I don’t think that is a good strategy to grow the economy.” By Thursday night, CNN’s Anderson Cooper was jabbering at length about the idea with law enforcement officials.

The issue of taxation just cropped up in another intriguing way. The Drug Enforcement Administration caused a stir in San Francisco on Wednesday when it raided a locally permitted medical marijuana dispensary. In part there was outcry because just days prior U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder had announced that the feds would no longer prosecute medical marijuana dispensaries where they are allowed under state and local law. So why the bust now?

So far the DEA isn’t sharing any details, but according to the San Francisco Chronicle, “A source in San Francisco city government who was informed about the raid said the DEA’s action appeared to be prompted by alleged financial improprieties related to the payment of sales taxes.”

It’s difficult to gauge the Chronicle’s anonymous source, but if accurate, the explanation seems rather odd. Last I checked, there was no national sales tax in the United States, so why would the federal government be interested in that issue? Moreover, while I’m not sure whether it applies to medical marijuana, prescription drugs are exempt under the current California sales tax regime.

The federal government does oversee interstate commerce, and U.S. border security, of course — perhaps better clues to the DEA’s continuing interest in the case. (Was supply at the SF pot club the real issue?) Which takes us back to the headline-grabbing drug war. You don’t have to stare for long at this DOJ threat assessment map tracking the Mexican cartels to notice the densely covered trajectory that runs the length of I-5, from San Diego to San Francisco to Seattle.

It’s no longer the war next door

Rising talk stateside about Mexico’s violent drug war has included a lot of buzz about potential “spillover” of the trouble — but it spilled over long ago, reaching far and wide. According to a report in December from the U.S. Department of Justice, the Mexican cartels maintain distribution networks or supply drugs to distributors in at least 230 American cities, from Orlando to Omaha to Anchorage. They control a greater portion of drug production, transportation and distribution than any other criminal group operating in the U.S., filling their coffers with billions of dollars a year.

Indeed, the war against the cartels is very much a Mexican-American one. Just take a look at this current threat assessment map from the National Drug Intelligence Center, showing U.S. cities implicated:

U.S. cities reporting the presence of Mexican drug trafficking, January 2006 - April 2008.

Violence has also been imported in no small quantity. Although the most sensational killings have taken place south of the border, brutal assaults, home invasions and murders connected with the drug trade have plagued U.S. cities and towns, particularly in the south but reaching as far north as Canada.

Buzz in Washington has also included the specter of Mexico becoming a “failed state.” Journalist and author Enrique Krauze says the talk is overblown. “While we bear responsibility for our problems,” he wrote this week, “the caricature of Mexico being propagated in the United States only increases the despair on both sides of the Rio Grande.” It is also profoundly hypocritical, he said.

America is the world’s largest market for illegal narcotics. The United States is the source for the majority of the guns used in Mexico’s drug cartel war, according to law enforcement officials on both sides of the border. Washington should support Mexico’s war against the drug lords — first and foremost by recognizing its complexity. The Obama administration should recognize the considerable American responsibility for Mexico’s problems. Then, in keeping with equality and symmetry, the United States must reduce its drug consumption and its weapons trade to Mexico.

Apparently this concept has reached the presidential level. At a prime time news conference on Tuesday otherwise dominated by discussion of the economy, President Obama reiterated a major border initiative unveiled earlier in the day and acknowledged: “We need to do even more to ensure that illegal guns and cash aren’t flowing back to these cartels.”

One way to help achieve that goal, it seems, would be to reconfigure policy with the recognition that the war on drugs as we know it is a proven failure.

Update: The San Francisco Chronicle reports about how cheap and easy it is to get high-powered assault rifles in Nevada. Many of them filter south to Mexican gangs by way of California. One of them was used to kill two police officers in Oakland on Saturday.

Mexico’s drug war, fully U.S. loaded

The raging drug war in Mexico is about to command even greater attention inside the United States. It’s not just the gruesome tales of drug cartel violence to the south; the U.S. is far more caught up in the maelstrom than many north of the border may care to realize.

Tuesday at the White House, Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano laid out Obama administration plans to throw additional money and manpower at the problem, amid mounting fears about “spillover” of corruption and violence into the U.S. On Wednesday, Napolitano will go to Capitol Hill specifically to address the crisis, while Secretary of State Hillary Clinton is scheduled to arrive in Mexico.

The administration is deploying big guns like Napolitano and Clinton with good reason. As the Wall Street Journal reported recently, “The government is girding for a possible Katrina-style disaster along the 2,000-mile-long Mexican border that would involve thousands of refugees flooding into the U.S. to escape surging violence in northern Mexico, or gun battles beginning to routinely spill across the border.” A recent story from international reporting start-up GlobalPost shows how joint U.S.-Mexican operations have been implicated in the spreading violence, on both sides of the border.

Some relatively obscure testimony by senior officials from the ATF and DEA to a Senate subcommittee last week contains stark details about our country’s role in the predicament. Simply put, the U.S. is serving as a vast weapons depot for the drug gangs. Because firearms are not readily available in Mexico, cash-wielding drug traffickers have gone north to obtain many thousands of them. According to the law enforcement leaders’ testimony, 90 percent of traceable seized weapons have come from the United States. The ATF reports disrupting the flow of more than 12,800 guns to Mexico since 2004.

Smuggled weapons seized last December in Texas. (Photo via U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.)

The weapons aren’t just coming from the U.S. border region. The law enforcement leaders cited a case from April 2008 in which 13 warring gang members were killed and five wounded: “ATF assisted Mexican authorities in tracing 60 firearms recovered at the crime scene in Tijuana,” they said. “As a result, leads have been forward to ATF field divisions in Denver, Houston, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Phoenix, San Francisco and Seattle.”

Sources of the weapons, they said, “typically include secondary markets, such as gun shows and flea markets since—depending on State law—the private sale of firearms at those venues often does not require background checks prior to the sale or record keeping.”

Military weapons are also a growing problem: “In the past six months we have noted a troubling increase in the number of grenades, which are illegal to possess and sell, seized from or used by drug traffickers, and we are concerned about the possibility of explosives-related violence spilling into U.S. border towns.”

Given that the global war on drugs is a proven failure, there was another striking aspect of the testimony: The top revenue generator for the Mexican cartels isn’t cocaine, heroin or other hard stuff. It’s… marijuana.

Napolitano’s message Tuesday included the assertion that the Obama administration is “renewing our commitment to reduce the demand for illegal drugs here at home.” That comes on the heels of Attorney General Eric Holder’s announcing that the federal government will no longer prosecute medical marijuana dispensaries in California and other states where they are legal under state law. With the prospect of a day trip to Ciudad Juarez looking increasingly like a visit to Kabul, and with the violence ricocheting northward, perhaps those who have been advocating fundamental changes in the nation’s marijuana laws will start to see some political traction for their ideas.

Mexico’s chilling drug war, at the door

In yesterday’s post about the chronically failing war on drugs, I didn’t mention Mexico — drug war-related problems just across the southern U.S. border have gotten big enough and scary enough to command their own focus. Mexico’s growing instability draws from a complex and long-running set of government and societal issues. But U.S. policy is a large and indisputable factor, and not just anti-drug policy. Indeed, our vast market for marijuana, cocaine and other illicit substances provides the criminal gangs with an endless river of cash. But even more troubling, our lax gun laws and prolific gun dealers supply them with stockpiles of nasty, sophisticated weaponry.

The contents of a new travel warning from the U.S. State Department posted in late February are nothing short of astonishing. The greatest increase in violence has occurred near the U.S. border. And it literally is a war:

Some recent Mexican army and police confrontations with drug cartels have resembled small-unit combat, with cartels employing automatic weapons and grenades. Large firefights have taken place in many towns and cities across Mexico but most recently in northern Mexico, including Tijuana, Chihuahua City and Ciudad Juarez.

The carnage, according to the State Department, has included “public shootouts during daylight hours in shopping centers and other public venues.” In Ciudad Juarez alone, just across the border from El Paso, Texas, Mexican authorities report that more than 1,800 people have been killed since January 2008.

Hot zones in Mexico's drug war. (Source: Wikimedia commons.)

According to a report in early March from “60 Minutes,” nearly 6,300 people were killed across Mexico last year in drug-related violence, double the amount of the prior year. There have been mass executions of policemen, kidnappings and beheadings. Mexico’s attorney general Eduardo Medina-Mora tells of weapons seizures including thousands of grenades, assault rifles and 50-caliber sniper rifles. The vast majority of them, he says, were acquired inside the United States.

Breaking the addiction to the drug war

In Vienna this Wednesday policy makers will convene once again to consider the United Nations strategy for battling illegal narcotics worldwide. It’s a war that is statistically impossible to win. A report today from the Guardian points to the massive cocaine trade out of Latin America to exemplify how the supply-side war on drugs is equivalent to shoveling water on an international scale:

The crucible is Colombia, the world’s main cocaine exporter. Since 2000 it has received $6 billion in mostly military aid from the US for the drug war. But despite the fumigation of 1.15m hectares of coca, the plant from which the drug is derived, production has not fallen. Across the whole of South America it has spiked 16%, thanks to increases in supply from Bolivia and Peru.

Says César Gaviria, Colombia’s former president and co-chair of the Latin American Commission on Drugs and Democracy: “Prohibitionist policies based on eradication, interdiction and criminalisation have not yielded the expected results. We are today farther than ever from the goal of eradicating drugs.”

Says Colonel René Sanabria, head of Bolivia’s anti-narcotic police force: “The strategy of the US here, in Colombia and Peru was to attack the raw material and it has not worked.”

Halfway around the world it’s the same story with the heroin trade out of Afghanistan.

Halfway around the world it’s the same story with the heroin trade out of Afghanistan.

Respected U.S. economists and judges agree: Our long-running drug policy with ideological roots tracing to Reagan and Nixon has gotten us nowhere.

If, as Tom Friedman argued yesterday, we have crossed a historic inflection point for fundamentally recasting our global economic paradigm, then it seems the costly war on drugs should be of a piece. There are no easy solutions, but there are promising alternatives to the status quo. A few years ago I reported an in-depth series for Salon examining “harm reduction” policy implemented in Vancouver, whose emphasis at a local level was on curbing drug demand and its attendant social problems. It appeared to work remarkably well.

There are signs the Obama administration might take things in a different direction. For his new director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy, President Obama reportedly has nominated Seattle police chief Gil Kerlikowske, whose views on drug policy seem decidedly more moderate than those of Bush-appointed hardliner John P. Walters. As the Guardian also notes today, a report last fall by the Government Accountability Office concluded the war on drugs had failed in Colombia — a report that was commissioned by then Senator Joe Biden.

Hard truths about the Iraq war

1. With such enormous problems at home, it is hard to focus on enormous problems beyond U.S. borders, even when we perceive the dangers of turning too inward.

2. It is hard not to be exhausted of and desensitized to the whole awful mess. A week from this Thursday, it will have been six years since George W. Bush launched “shock and awe.” For the vast majority of Americans who have no direct connection to the war, if we are brutally honest with ourselves, it is hard in some respects to care at this point. (More on this below.)

3. It is but one of two daunting wars we are fighting. (And the new president is poised to make the other one larger.)

4. It is far, far from over.

Despite items one and two above, distinguished military reporter Thomas Ricks had some tranfixing things to say about the war on Wednesday, during an interview on NPR about his new book. Ricks’ comments are likely to prove distinct from the White House talking points and news coverage that will mark the six-year anniversary of the conflict in the coming days. His reporting in Iraq, including interviews in 2008 with Ambassador Ryan Crocker, the top U.S. diplomat there, left Ricks to conclude, “The events for which this war will be remembered have not yet happened.” Here’s a bit more of what was most striking among his comments, from the forbidding magnitude of the problem to some startling attitudes about the war that Ricks encountered while promoting his book recently in the liberal-by-reputation Bay Area:

Despite items one and two above, distinguished military reporter Thomas Ricks had some tranfixing things to say about the war on Wednesday, during an interview on NPR about his new book. Ricks’ comments are likely to prove distinct from the White House talking points and news coverage that will mark the six-year anniversary of the conflict in the coming days. His reporting in Iraq, including interviews in 2008 with Ambassador Ryan Crocker, the top U.S. diplomat there, left Ricks to conclude, “The events for which this war will be remembered have not yet happened.” Here’s a bit more of what was most striking among his comments, from the forbidding magnitude of the problem to some startling attitudes about the war that Ricks encountered while promoting his book recently in the liberal-by-reputation Bay Area:

On the time frame we face:

“I think we may just be halfway through this war. I know President Obama thinks he’s going to get all troops out by the end of 2011. I don’t know anyone in Baghdad who thinks that’s going to happen. I think Iraq is going to change Obama more than Obama changes Iraq.”

On the scope of the disaster:

“The original U.S. war plan was to be down to 30,000 troops by September 2003…. I do think this war was the biggest mistake in the history of American foreign policy. I think it’s a tragedy. I think George Bush’s mistakes are something we’re going to be paying for for decades. We don’t yet understand how big a mistake this is.”

On the destructive prospects of the U.S. military pulling out:

“I think Americans are really sick of the Iraq war…. I was speaking in California last week, near liberal Mill Valley, and I said, Look, if you leave right now this could lead to genocide. And somebody in the audience said, ‘So what.’ And somebody else said, ‘Genocide happens all the time.’ And I thought, my god, Americans are willing to take genocide in Iraq, and just leave.”

Truth and fantasy among the Slumdogs

Not surprisingly, “Slumdog Millionaire,” director Danny Boyle’s frenetic tale springing from the vast underbelly of Mumbai, swept the Academy Awards last night. The film was suited to the national mood, with its combustible mix of corruption and class warfare, despair and materialistic hope. The Academy has done worse in years past; on the whole “Slumdog” is an engaging ride, and at times an extraordinary visual postcard from a world mostly unseen by those in the West. The film’s biggest problem is a narrative one, as it struggles to reconcile competing forces of hard-hitting realism and romantic fantasia.

The same might be said of Katherine Boo’s timely feature story in the Feb. 23 issue of the New Yorker, “Opening Night.” Boo reports from Gautum Nagar, one of numerous large slums squeezed around Mumbai’s international airport. Set on the night of the Indian premiere of “Slumdog Millionaire,” her story traces the fortunes of a 13-year-old boy named Sunil, who has turned from airport garbage scavenger (a primary trade in the slum) to scrap metal thief after the global economic crisis has pummeled the local recycling business.

Boo is an award-winning journalist who has reported extensively from poverty-stricken front lines, and “Opening Night” is a compelling read dotted with insights about the effects of globalization. Yet, I couldn’t help but wonder about certain passages in which Boo ascribes intellectual and lyrical qualities to Sunil’s thinking that seem to strain belief. In several scenes she takes us deep inside his mind:

Sunil still did not feel much like a thief. When he took a bath in an abandoned pit at the concrete-mixing plant, he pushed away the algae to inspect his reflection. The change in his profession didn’t yet show on his face: same big mouth, wide nose, problem torso. He was too small all over.

And when recounting Sunil’s thievery at a newly constructed airport parking garage:

The roof had two kinds of space, really. One kind was what a boy got when he stood exactly in the middle and knew that even if his arms were ten times longer he’d touch nothing if he spun around. But that kind of space would be gone when the garage was open and filled with cars. The space that would last was the kind he leaned into, over the guardrails.

From a writing standpoint this is the recognizable stuff of fiction, prose concerned foremost with thematic imagery and character depicted in the service of narrative. That’s not to say that it isn’t truthful to what Boo may have learned during what clearly was a devoted and exhaustive journey into India’s underclass. (According to the magazine’s contributor notes, she has spent the past 14 months reporting from the Mumbai slums for a forthcoming book.) But particularly in an era when the blurring of nonfiction and fiction has turned up some serious stinkers, Boo takes some intriguing risks with her reportage in this respect. We do learn late in the piece that Sunil was to some degree “privileged,” having been taken in for a period by a Catholic charity for private schooling outside the city. Still, given his age and background it seems unlikely that he would have thought or been able to express himself in such sophisticated terms, even to a highly talented journalist who apparently spent much time in his company.

The New Yorker has also posted a video montage from Boo’s trip, a rather striking contrast to the high-gloss footage that just scored eight golden statues.

Obama’s next epic crisis on the horizon

Sure, the Dow is hitting new lows and the economic meltdown is looking pretty damn frightening. (If the recent flood of headlines hasn’t made you want to hide in a hole, just read Paul Krugman’s mostly despairing analysis today.) But for the new president the trouble is only just beginning, as dark clouds gather to the east. Iran, it seems, is accelerating down a path toward nuclear weapons. That’s troubling in its own right — but far more so when adding to the mix a new right-wing government in Israel, the possibility of which looks imminent as hardliner Benjamin Netanyahu gains an edge in the country’s close election.

In late 2007, my friend and fellow journalist Gregory Levey took an in-depth look at Netanyahu’s political resurgence and the regional conflict that potentially could be unleashed if he returned to power. (This would be his second time as prime minister, having served from 1996-1999.) For anyone in the Israel peace camp, it would be an understatement to say that the prospect did not bode well. And now Iran may be even closer to being perceived truly as an immediate and existential threat. So while President Obama, admirably, has been signaling interest in a new era of diplomacy with the Iranians, he soon may be facing a much more dangerous brew in the Middle East.

Toxic banks one-up bin Laden

I’ve been thinking about the economic crisis as a rising national security danger since sometime back in December, and I’m sure I haven’t been alone, even though scant attention has been paid in the mainstream media — until now. It’s only an odd coincidence that the same day earlier this week that I was suggesting we’d soon be hearing more from President Obama’s intelligence chief on the matter, Dennis C. Blair was in fact on Capitol Hill sounding the alarm. The global economic crisis now represents the top security threat to the United States, he told the Senate Intelligence Committee on Thursday.

“Roughly a quarter of the countries in the world have already experienced low-level instability such as government changes because of the current slowdown,” Blair said. (That would be nearly 50 countries. Including Iceland, whose government collapsed three weeks ago.) Blair further warned of the kind of “high levels of violent extremism” seen in the 1920s and 1930s if the economic crisis persists beyond 2009.

The fears have now reached the front page of Sunday’s New York Times: “Unemployment Surges Around the World, Threatening Stability.” The trio of images above the fold are a quick world tour of worker displacement and unrest, from Bejing to Reykjavik to Santiago, where street graffiti declares “unemployment is humiliation.”

Ivan Alvarado/Reuters

Just one glaring manifestation of a troubling global trend.

Leave a comment

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.