Archive for the ‘culture’ Category

America loves doga! (Or, a brief meditation on the dubious trend story)

It’s a kind of yoga. You do it with your dog. No, seriously. Together with your pooch you stretch, you meditate, you pose. The New York Times reported on this recently. Maybe you’d already heard about it, but probably not. (More on that in a minute.) For an hour or so on the evening of April 8 the story was featured, replete with large photo, atop the leading news site. It was number one on the Times’ list of most e-mailed stories for a couple days thereafter. Apparently doga is a rising trend in America, worthy of much attention.

Or is it? Indeed, there’s a bit of a journalism issue here, but first things first: Sure, the pictures of the dogs were pretty cute and/or pretty funny, and who doesn’t love cute-funny dogs, and who wouldn’t click gleefully on a slide show with additional pictures of cute-funny dogs, thereby contributing to what certainly must’ve been a big spike in page views for nytimes.com.

There’s probably not much reason to add that partner yoga with your dog may sound like one of the more inane things you’ve ever heard of, because others are likely to say that (yogis among them), as well as to suggest that the dogs involved may well be feeling less than enlightened by the activity, and anyway, the photos (by Michael Nagle) from the Times’ slide show really do speak for themselves:

There is good reason to add, however, that claims about doga’s growing popularity across the land seem howlingly suspect. Behold the all too common trend story that offers no real evidence of a trend.

After a brief opening anecdote about a few people in Chicago, New York and Seattle variously contorting with their Jack Russell terriers and Shih Tzus, the Times report says this of doga (emphasis mine):

Ludicrous? Possibly. Grist for anyone who thinks that dog-owners have taken yoga too far? Perhaps. But nationwide, classes of doga — yoga with dogs, as it is called — are increasing in number and popularity. Since Ms. Caliendo, a certified yoga instructor in Chicago, began to teach doga less than one year ago, her classes have doubled in size.

That’s it, folks. The rest of the article contains no further quantitative information about the purported legions of spiritually enlightened pet owners caught up in the craze.

Perhaps the Times reporter spotted some sort of trend in other stories about the alleged trend: The Associated Press covered it back in 2007, and ABC News published a story on April 1 (whose date apparently was a coincidence, although you could be forgiven for thinking the story was fake.) ABC included San Francisco and Jacksonville, Fla., on the list of locales and described a few doga accessories being sold. But no hard numbers there, either. Instead, the story leaned on “pet trend expert” Maggie Gallant to claim that doga “has the potential to be a very widespread trend.” As Gallant panted, “There are 75 million homes in America that have dogs and about 13 million people practicing yoga.”

Kudos to Chicago Tribune columnist Mary Schmich for sniffing out the truth. With a little follow-up reporting, she discovered that the Chicago locale cited in the Times article — the one where classes “have doubled in size” — now offers one doga class a week, with three to 12 students in each.

Aside from whatever benefits may lie in store for dog owners who team up with their beloved furry ones for stretching and meditation, it seems that America’s big embrace of doga turns out to be, well, a particular kind of scoop indeed.

This is David Foster Wallace

On Tuesday, Little, Brown and Company publishes a book version of “This Is Water: Some Thoughts, Delivered on a Significant Occasion, about Living a Compassionate Life,” the celebrated commencement speech David Foster Wallace gave to the 2005 graduating class at Kenyon College. The pocket-sized book breaks up the nearly 4,000-word speech into digestible pieces on the page, some as brief as a single phrase. It’s an intriguing approach: In one sense, practical to publishing the essay in book form while drawing out its epigrammatic layers. At the same time, it seems rather un-DFW — contrary to the hyper-digressive, cascading prose for which he is so well-known.

Wallace giving a reading in 2006 in San Francisco. (Wikimedia Commons.)

Whether Wallace would approve of the presentation we probably can’t know. But it highlights a radiant directness that was often in danger of obscuring beneath his towering intellect. (It’s worth noting that there are some subtle differences to be found in other versions of the commencement speech floating out there; I contacted the publisher seeking clarification on how the text was prepared, but a publicist responded that Wallace’s longtime editor, Michael Pietsch, was declining to be interviewed about the book.)

Wallace’s focus was on the far from easy task of living life consciously in the adult world. He begins with a “didactic little parable-ish story,” as he puts it, about young fish who are oblivious to the environs through which they swim. More than just challenging the conventions of the commencement genre, Wallace makes use of them with a fierce sincerity: “I submit that this is what the real, no-bullshit value of your liberal arts education is supposed to be about: How to keep from going through your comfortable, prosperous, respectable adult life dead, unconscious, a slave to your head and to your natural default setting of being uniquely, completely, imperially alone, day in and day out.”

Segments like these carry an added poignancy in the wake of Wallace’s death by suicide last fall at the age of 46. Rather than a matter of morality or religion or the afterlife, he went on to tell the young graduates, “the capital-T Truth is about life before death. It is about making it to thirty, or maybe even fifty, without wanting to shoot yourself in the head.”

More striking, though, is his evocative insight and humor. If the students really do learn how to think and pay attention in life, he tells them, “It will actually be within your power to experience a crowded, hot, slow, consumer-hell-type situation as not only meaningful, but sacred, on fire with the same force that made the stars — compassion, love, the subsurface unity of all things. Not that that mystical stuff’s necessarily true: The only thing that’s capital-T True is that you get to decide how you’re going to try to see it.”

The pleasure of experiencing Wallace’s speech again underscored a realization I had when reading D.T. Max’s lengthy look back at Wallace’s life: The world deserves a published collection of David Foster Wallace’s correspondences, too. Various bits of it appearing in the recent New Yorker article — with fellow writer Jonathan Franzen, his literary agent Bonnie Nadell and others — cast additional light on Wallace’s humanity and highly emotive lexicon.

While I’ve admired some of his fiction, I’ve always thought Wallace was at his best with essays and literary journalism; as I wrote about here recently, gems found in his private correspondences show how the epistolary form (actual letters as well as email) brought out a more direct spirit of his, too.

The back cover of “This Is Water” asserts that the essay was Wallace’s answer to “the challenge of collecting all he believed about life and lasting fulfillment into a brief talk.” The inflated language of marketing copy, it would seem — Wallace’s prolific, restive consciousness probably could never be so perfectly distilled. A deeper look at his personal correspondences, meanwhile, could only add to the picture of a life and work tragically cut short and revered by so many.

On Mark Bowden’s NYT takedown

The so-called crisis in the news industry sure has generated some sensational stories of late. “American journalism is in a period of terror,” announces Mark Bowden in a tome of an article appearing in the May issue of Vanity Fair. Mostly a deft hatchet job on Arthur Sulzberger Jr., the publisher of the New York Times, Bowden’s piece sent the media cognoscenti into a tizzy, although nobody seems to have noticed its one truly illuminating segment.

Photo illustration from Vanity Fair.

Even the mighty Times is facing financial peril these days, and Bowden’s premise is that the newspaper scion “has steered his inheritance into a ditch.” He abuses tools of the trade to help suggest his case. As one unnamed “industry analyst” tells us, “Arthur has made some bad decisions, but so has everyone else in the business. Nobody has figured out what to do.” Earth shattering. Perhaps Bowden should pick up a copy of the Times and read Clark Hoyt on the suitable use of anonymous sources. For a substantive take on contemporary debacles across the business, check out this recent piece by Daniel Gross.

In fact, I’m a big fan of Bowden’s. Right now I happen to be reading his 2006 book “Guests of the Ayatollah,” a riveting account of the Iran hostage crisis. Particularly in the realm of national security, few reporters are as exhaustive, persuasive — and downright exciting to read — as him.

On the media, not so much. There he has tended toward the self-involved, maybe a particular pitfall for great reporters covering their own vocation. (See the opening line of the Sulzberger article, which zooms in directly on… Bowden himself, as he receives a phone call from Sulzberger: “I was in a taxi on a wet winter day in Manhattan three years ago…” Especially telling, I think, given that in another recent piece orbiting the news business, a profile of David Simon, Bowden also wrote himself prominently into the narrative.) The Vanity Fair article is exquisitely timed with the accelerating upheaval in the newspaper industry, and reads mostly like, well, a salacious, insider-y Vanity Fair article.

And yet, buried deep in the 11,500 words is one of the best analogies I’ve encountered anywhere conveying the potential for digital journalism:

When the motion-picture camera was invented, many early filmmakers simply recorded stage plays, as if the camera’s value was just to preserve the theatrical performance and enlarge its audience. To be sure, this alone was a significant change. But the true pioneers realized that the camera was more revolutionary than that. It freed them from the confines of a theater. Audiences could be transported anywhere. To tell stories with pictures, and then with sound, directors developed a whole new language, using lighting and camera angles, close-ups and panoramas, to heighten drama and suspense. They could make an audience laugh by speeding up the action, or make it cry or quake by slowing it down. In short, the motion-picture camera was an entirely new tool for storytelling.

Bowden uses the comparison in the service of whacking Sulzberger — but it also points directly to a broader stagnation in media companies’ use of the digital platform. There is experimentation going on, but often without much imagination: Digital video clips are all the rage? OK, we’ll put reporters on camera describing the stories they’ve just published! Online communities and reader interactivity are the latest buzz? OK, we’ll feature the shouting matches in our comments threads as actual news!

The rising multimedia and publishing capabilities of the digital realm are charged with promise, and demand deeper thinking about their optimal use. With any given subject, which digital tools are most effective for gathering information and telling the story? How can the information-rich ecosystem of the Web enhance the knowledge gained? What new ways are there to produce reliable, authoritative and compelling content, taking maximum advantage of a decentralized and participatory technology like no other we’ve ever known?

Soon enough we may all be getting our news on a kind of flexible digital paper. The possibilities for what it could contain are big, and they’re just beginning.

UPDATE: Mark Bowden responds.

Waking up to America’s economic nightmare

With the roughly 1,500-point rise in the Dow Jones average since early March, it seems investors have been dreaming about the good old days. This Bloomberg chart from last Thursday’s trading marks the apparent disconnect — you don’t have to be a stock market maven to sense that the dramatic rally will likely prove to be, in the parlance of Wall Street, the kaput kitty hitting the pavement.

With the roughly 1,500-point rise in the Dow Jones average since early March, it seems investors have been dreaming about the good old days. This Bloomberg chart from last Thursday’s trading marks the apparent disconnect — you don’t have to be a stock market maven to sense that the dramatic rally will likely prove to be, in the parlance of Wall Street, the kaput kitty hitting the pavement.

Take your pick of grim indicators. For the last two months the Consumer Confidence Index has plumbed its lowest depths since its inception in 1967. As we learned Friday, the nation lost another 663,000 jobs in March, bringing the total to 5.1 million since the recession began in December 2007. Unemployment may be a lagging economic indicator, but there’s little to suggest that the wave is cresting or will be any time soon.

But the worst sign of all right now may be this: America is still stuck in the anger stage. Recently I overheard a classic strain of the outrage in a coffee shop in Noe Valley (hardly ground zero for hard times), in a conversation between two rather comfortable looking middle-aged adults. One was wailing away on America’s preferred punching bag, Mr. Wall Street Executive, for “raping the taxpayers” without remorse. His hair was so on fire that I feared his head might actually explode. Soon the talk hit on the hypocrisy of the Obama administration’s forcing General Motors chief Rick Wagoner to fall on his sword while Wall Street’s lords of finance so unfairly kept feasting on federal bailout funds. Somehow the disastrous story of the SUV-bloated American auto industry didn’t come up.

Indeed, we must also be in a recession of genuine awareness. While New York Times columnist Frank Rich can himself be shrill at times, he’s got it right regarding the continuing blame game:

Why is there any sympathy whatsoever for a Detroit C.E.O. who helped wreck his company, ruined investors and cost thousands of hard-working underlings their jobs, when there is no mercy for those who did the same on Wall Street? Might we, too, have a double standard? Could we still be in denial of the reality that greed and irresponsibility were not an exclusive Wall Street franchise during our national bender?

A prominent financial expert I interviewed last week for a forthcoming magazine piece on the economic crisis said to me at one point in our conversation, “Almost everybody who was part of the system failed.” He wasn’t only talking about Wall Street institutions, government regulators and the media.

Easily enough we get whipped into a frenzy over unjust executive bonuses or the sins of the media’s prime time ding-dongs. But what of America’s common financial lifestyle over the last two decades? As Rich continues, in answer to his own question: “Any citizen or business that overspent or overborrowed in the bubble subscribed to its reckless culture. That culture has crumbled everywhere now, and a new economic order will have to rise from its ruins.”

Even better put, it will have to be built from them. That will be painstaking, no doubt — block by block, brick by brick, as has been said by a certain someone. But right now, it seems, too many people are still standing on the outskirts shouting about who plundered the village, rather than heading into the collective rubble and really starting to pick up the pieces.

UPDATE: On a related note, Wall Street conspiracy theorists and/or Hollywood screenwriters will find plenty of grist in this Times front-pager on Larry Summers’ enriching hedge fund days at D.E. Shaw prior to joining Team Obama:

D. E. Shaw does not like to talk about what goes on inside its modish headquarters near Times Square. There, esoteric trading strategies are imagined, sketched on whiteboards and modeled on supercomputers by an elite corps of math wizards and scientists, most of them unknown to the outside world….

At Shaw, Mr. Summers, the professor, was often the student. The arrogant personal style that turned off some Harvard colleagues seemed to evaporate, Shaw traders say. Mr. Summers immersed himself in dynamic hedging, Libor rates and other financial arcana.

He seemed to fit in among Shaw’s math-loving “quants,” as devotees of math-heavy quantitative investing are known. Traders joked that Mr. Summers was the first quant Treasury secretary because he had once ordered dollar bills to be printed with the transcendental number pi — 3.14159… — as the serial number.

Paging Dan Brown and Ron Howard?

Guardian’s Twitter move, GM’s bailout madness

It’s adding up to a strange day in the news, my friends, but then again these are no ordinary times.

The venerable 188-year-old Guardian, apparently seeing the ugly writing on the wall for the media business, has taken perhaps the boldest step yet to embrace digital technology. Will such an all-in bet on rapid-fire reporting pay off?

Meanwhile, in the heart of Silicon Valley, a hotshot entrepreneur has moved to capitalize on social networking technology in a different cutting-edge way. If the producers of “The Bachelor” take notice, look out for a full convergence of reality TV and the Internets even sooner than already anticipated.

Meanwhile, in the heart of Silicon Valley, a hotshot entrepreneur has moved to capitalize on social networking technology in a different cutting-edge way. If the producers of “The Bachelor” take notice, look out for a full convergence of reality TV and the Internets even sooner than already anticipated.

And in what can only really be considered a desperate move, General Motors apparently is grasping for a solution to its epic troubles by way of two well-known, if irritating, car experts.

More odd stuff going on across the pond.

Seeing Obama’s burden, the drug war and more

Even in the loquacious realm known as the blogosphere, it is possible at times to lack words. Or to feel that there are simply too many of them. Either way, Daryl Cagle’s Political Cartoonists Index offers a pleasing alternative. Here are three recent entries that caught my eye.

Hajo (Amsterdam), on President Obama’s economic travails:

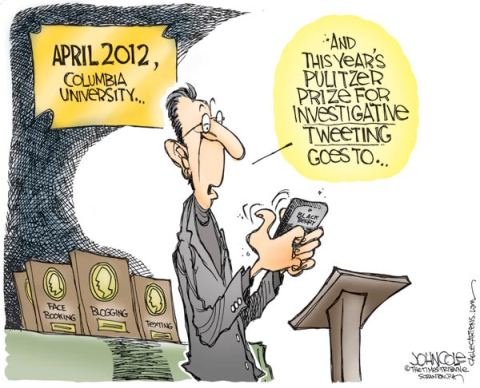

John Cole (Scranton, PA), peering into journalism’s truncated future:

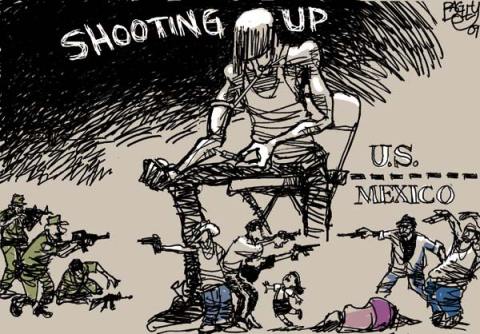

Pat Bagley (Salt Lake City), a potent take on the Mexican-American drug war:

The month the news broke

It may be that we’ll look back at March 2009 as a pivotal time in the erratic but inexorable transition from print to digital news. In some ways it’s very much a slow-motion revolution, beginning perhaps as long ago as 1981, and far from over. But this month has been striking both for the destruction in the newspaper industry and the hum of activity focused on the digital future.

It’s the latter that matters more. NYU media maven Jay Rosen has pulled together an essential roundup for anyone interested in diving deep into the discussion. Rosen credits a March 13 essay by Clay Shirky with triggering a flurry of writing; he summarizes a dozen recent pieces that build out the picture. I haven’t read them all yet, but in addition to Shirky’s piece I highly recommend Steven Berlin Johnson’s Old Growth Media and the Future of News, which he presented at the South By Southwest Interactive Festival in Austin. His use of ecosystems as a metaphor for the digital transformation is enlightening in multiple ways, while smartly avoiding utopianism:

It’s the latter that matters more. NYU media maven Jay Rosen has pulled together an essential roundup for anyone interested in diving deep into the discussion. Rosen credits a March 13 essay by Clay Shirky with triggering a flurry of writing; he summarizes a dozen recent pieces that build out the picture. I haven’t read them all yet, but in addition to Shirky’s piece I highly recommend Steven Berlin Johnson’s Old Growth Media and the Future of News, which he presented at the South By Southwest Interactive Festival in Austin. His use of ecosystems as a metaphor for the digital transformation is enlightening in multiple ways, while smartly avoiding utopianism:

Now there’s one objection to this ecosystems view of news that I take very seriously. It is far more complicated to navigate this new world than it is to sit down with your morning paper. There are vastly more options to choose from, and of course, there’s more noise now. For every Ars Technica there are a dozen lame rumor sites that just make things up with no accountability whatsoever. I’m confident that I get far more useful information from the new ecosystem than I did from traditional media a long fifteen years ago, but I pride myself on being a very savvy information navigator. Can we expect the general public to navigate the new ecosystem with the same skill and discretion?

Indeed, as Johnson suggests, information consumers may yet crave the guidance of authoritative institutions, including… newspapers. Some of which now command some of the largest online audiences. But many of them have been failing in the vision department, as Alan Mutter pointed out early this month:

As a direct consequence of the breakdown in the traditional media business model, publishers today are cutting the quality and quantity of the content they produce at the very moment they should be investing more aggressively than ever … As the most challenged of all the distressed media companies, newspapers are so strapped today that they are producing ever less original reporting … This is not merely a step in the wrong direction. It is a leap into the abyss.

As the fresh experiment with The P-I in Seattle seems to indicate so far, taking a newspaper all-digital while cutting its news gathering capacity by roughly 80 percent is not a great way to proceed.

While there is still plenty of handwringing going on, in my view the essays gathered by Rosen evoke daybreak far more than twilight. And March 2009 is ending on a bright note, at least symbolically. Ever since its election-year rise, the opinion-laden Huffington Post has been touted as a model for future journalism — never mind that it doesn’t pay most contributors and produces almost zero original reporting. Late yesterday the publication announced a new turn: the launch of a $1.75 million investigative reporting initiative.

Ricky Gervais goes toe to toe with Elmo

So what happens when a friendly little red monster sits down with a top British comedian for an interview? Mayhem, of course.

Outtakes from Ricky Gervais’ visit to “Sesame Street,” an appearance to be aired during the show’s 40th anniversary this fall, have been floating around recently on the Web. It’s potent stuff, and probably works well as an antidote to, say, lingering rage about AIG, or worries about the invasive drug war, or the grim economic headlines, or personal pain from the recession, or etc.

Outtakes from Ricky Gervais’ visit to “Sesame Street,” an appearance to be aired during the show’s 40th anniversary this fall, have been floating around recently on the Web. It’s potent stuff, and probably works well as an antidote to, say, lingering rage about AIG, or worries about the invasive drug war, or the grim economic headlines, or personal pain from the recession, or etc.

A little over a year ago I had the pleasure of spending a day watching Gervais work and interviewing him at length for a magazine profile. He was thoughtful and engaging, and at turns quite zany. But really I had no idea.

“Elmo is so glad Mr. Ricky Gervais is here,” the little guy chirps at the outset, and it’s quickly downhill from there. Soon Elmo admonishes a producer off camera. “Where did you lose this interview?” he demands. “Where? Where?”

“You call yourself professional,” Gervais retorts. “You can’t even control a muppet and a fat guy. Just calm down.”

Both are in top form — Elmo with his radiant third-person observations of self, Gervais with his ever tasteful subversiveness. Elmo points out that the dust-up “wasn’t Elmo’s fault,” and things ratchet back down a notch. But Gervais can’t let it rest. “Listen,” he says, “these are the no-go areas: Drugs. Child Abuse. The Holocaust. OK? Let’s stay off those three things.”

His riff about necrophilia probably won’t make final cut, either. Enjoy.

It’s no longer the war next door

Rising talk stateside about Mexico’s violent drug war has included a lot of buzz about potential “spillover” of the trouble — but it spilled over long ago, reaching far and wide. According to a report in December from the U.S. Department of Justice, the Mexican cartels maintain distribution networks or supply drugs to distributors in at least 230 American cities, from Orlando to Omaha to Anchorage. They control a greater portion of drug production, transportation and distribution than any other criminal group operating in the U.S., filling their coffers with billions of dollars a year.

Indeed, the war against the cartels is very much a Mexican-American one. Just take a look at this current threat assessment map from the National Drug Intelligence Center, showing U.S. cities implicated:

U.S. cities reporting the presence of Mexican drug trafficking, January 2006 - April 2008.

Violence has also been imported in no small quantity. Although the most sensational killings have taken place south of the border, brutal assaults, home invasions and murders connected with the drug trade have plagued U.S. cities and towns, particularly in the south but reaching as far north as Canada.

Buzz in Washington has also included the specter of Mexico becoming a “failed state.” Journalist and author Enrique Krauze says the talk is overblown. “While we bear responsibility for our problems,” he wrote this week, “the caricature of Mexico being propagated in the United States only increases the despair on both sides of the Rio Grande.” It is also profoundly hypocritical, he said.

America is the world’s largest market for illegal narcotics. The United States is the source for the majority of the guns used in Mexico’s drug cartel war, according to law enforcement officials on both sides of the border. Washington should support Mexico’s war against the drug lords — first and foremost by recognizing its complexity. The Obama administration should recognize the considerable American responsibility for Mexico’s problems. Then, in keeping with equality and symmetry, the United States must reduce its drug consumption and its weapons trade to Mexico.

Apparently this concept has reached the presidential level. At a prime time news conference on Tuesday otherwise dominated by discussion of the economy, President Obama reiterated a major border initiative unveiled earlier in the day and acknowledged: “We need to do even more to ensure that illegal guns and cash aren’t flowing back to these cartels.”

One way to help achieve that goal, it seems, would be to reconfigure policy with the recognition that the war on drugs as we know it is a proven failure.

Update: The San Francisco Chronicle reports about how cheap and easy it is to get high-powered assault rifles in Nevada. Many of them filter south to Mexican gangs by way of California. One of them was used to kill two police officers in Oakland on Saturday.

Mexico’s drug war, fully U.S. loaded

The raging drug war in Mexico is about to command even greater attention inside the United States. It’s not just the gruesome tales of drug cartel violence to the south; the U.S. is far more caught up in the maelstrom than many north of the border may care to realize.

Tuesday at the White House, Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano laid out Obama administration plans to throw additional money and manpower at the problem, amid mounting fears about “spillover” of corruption and violence into the U.S. On Wednesday, Napolitano will go to Capitol Hill specifically to address the crisis, while Secretary of State Hillary Clinton is scheduled to arrive in Mexico.

The administration is deploying big guns like Napolitano and Clinton with good reason. As the Wall Street Journal reported recently, “The government is girding for a possible Katrina-style disaster along the 2,000-mile-long Mexican border that would involve thousands of refugees flooding into the U.S. to escape surging violence in northern Mexico, or gun battles beginning to routinely spill across the border.” A recent story from international reporting start-up GlobalPost shows how joint U.S.-Mexican operations have been implicated in the spreading violence, on both sides of the border.

Some relatively obscure testimony by senior officials from the ATF and DEA to a Senate subcommittee last week contains stark details about our country’s role in the predicament. Simply put, the U.S. is serving as a vast weapons depot for the drug gangs. Because firearms are not readily available in Mexico, cash-wielding drug traffickers have gone north to obtain many thousands of them. According to the law enforcement leaders’ testimony, 90 percent of traceable seized weapons have come from the United States. The ATF reports disrupting the flow of more than 12,800 guns to Mexico since 2004.

Smuggled weapons seized last December in Texas. (Photo via U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.)

The weapons aren’t just coming from the U.S. border region. The law enforcement leaders cited a case from April 2008 in which 13 warring gang members were killed and five wounded: “ATF assisted Mexican authorities in tracing 60 firearms recovered at the crime scene in Tijuana,” they said. “As a result, leads have been forward to ATF field divisions in Denver, Houston, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Phoenix, San Francisco and Seattle.”

Sources of the weapons, they said, “typically include secondary markets, such as gun shows and flea markets since—depending on State law—the private sale of firearms at those venues often does not require background checks prior to the sale or record keeping.”

Military weapons are also a growing problem: “In the past six months we have noted a troubling increase in the number of grenades, which are illegal to possess and sell, seized from or used by drug traffickers, and we are concerned about the possibility of explosives-related violence spilling into U.S. border towns.”

Given that the global war on drugs is a proven failure, there was another striking aspect of the testimony: The top revenue generator for the Mexican cartels isn’t cocaine, heroin or other hard stuff. It’s… marijuana.

Napolitano’s message Tuesday included the assertion that the Obama administration is “renewing our commitment to reduce the demand for illegal drugs here at home.” That comes on the heels of Attorney General Eric Holder’s announcing that the federal government will no longer prosecute medical marijuana dispensaries in California and other states where they are legal under state law. With the prospect of a day trip to Ciudad Juarez looking increasingly like a visit to Kabul, and with the violence ricocheting northward, perhaps those who have been advocating fundamental changes in the nation’s marijuana laws will start to see some political traction for their ideas.

Light in the darkness of David Foster Wallace

A prodigious amount has been written about David Foster Wallace since the heart-rending news of his suicide last September. The outpouring continues. This week, a humorous essay that keyed off Wallace’s hyper-baroque writing has seen a viral revival on the Web. Earlier this month, the New Yorker published a lengthy epilogue along with an excerpt from Wallace’s unfinished novel, “The Pale King.” His much-admired speech to the 2005 graduating class at Kenyon College in Ohio will come out in book form in April.

I finally had time to read the long New Yorker piece, and it made me realize that the world also deserves a published collection of Wallace’s correspondence, with fellow writer Jonathan Franzen, his literary agent Bonnie Nadell and others. The varied bits of it appearing in the New Yorker cast additional light on his humanity and highly emotive lexicon.

Steve Liss/Getty/Time Life

There is much insight and lyricism to be found in Wallace’s fiction, but it can be hard to track down and enjoy amid all the dense, cerebral text. He played language not as an instrument but as a postmodern orchestra, and it could get too cacophonous. (I remember when Bob Watts gave me his hardcover copy of “Oblivion,” barely cracked into. “Couldn’t really do it,” he said.) Although I much admired some of Wallace’s earlier short stories, I’ve always thought that he was at his best with essays and literary journalism. It seems the epistolary form (actual letters as well as email) brought out a more direct spirit of his, too, however painful. While in a deep rut in May 1990 he wrote to Franzen:

Right now, I am a pathetic and very confused young man, a failed writer at 28 who is so jealous, so sickly searingly envious of you and [William] Vollmann and Mark Leyner and even David fuckwad Leavitt and any young man who is right now producing pages with which he can live, and even approving them off some base clause of conviction about the enterprise’s meaning and end.

There was also a vivid kind of humor: In another correspondence with Franzen about 15 years later, this time regarding his struggles with “The Pale King,” Wallace wrote, “The whole thing is a tornado that won’t hold still long enough for me to see what’s useful and what isn’t … I’ve brooded and brooded about all this till my brooder is sore.”

One of his former editors recalls Wallace also comparing the writing of the novel with “trying to carry a sheet of plywood in a windstorm.”

For me, one of Wallace’s most memorable essays was published in August 2006 in the magazine Play, in which he profiled tennis titan Roger Federer.

A top athlete’s beauty is next to impossible to describe directly. Or to evoke. Federer’s forehand is a great liquid whip, his backhand a one-hander that he can drive flat, load with topspin, or slice — the slice with such snap that the ball turns shapes in the air and skids on the grass to maybe ankle height. His serve has world-class pace and a degree of placement and variety no one else comes close to; the service motion is lithe and uneccentric, distinctive (on TV) only in a certain eel-like all-body snap at the moment of impact. His anticipation and court sense are otherworldly, and his footwork is the best in the game — as a child, he was also a soccer prodigy. All this is true, and yet none of it really explains anything or evokes the experience of watching this man play. Of witnessing, firsthand, the beauty and genius of his game. You more have to come at the aesthetic stuff obliquely, to talk around it, or — as Aquinas did with his own ineffable subject — to try to define it in terms of what it is not.

It remains a memorable passage because it illumes not only Wallace’s profound talent, but also, in some sense, the linguistic-spiritual puzzle he died still trying to solve. He tells you it can’t be done and then he nearly does it, brilliantly. A deeper look at his personal correspondences — when presumably he was writing more free of the crushing performance pressures he put on himself — could only add to the picture.

The revolution will be further digitized

A large newspaper in a major American city has just gone all-digital. Depending on how you choose to look at it, the occasion is either tragic or revolutionary.

The 146-year-old Seattle Post-Intelligencer printed its last edition on Tuesday, becoming an Internet-only news source. In a report on its own Web site, the “paper” described the contours of the new, much smaller operation now in place. The P-I, as it’s called, is a “community platform” that will feature “breaking news, columns from prominent Seattle residents, community databases, photo galleries, 150 citizen bloggers and links to other journalistic outlets.” The New York Times notes that The P-I “will resemble a local Huffington Post more than a traditional newspaper,” with a news staff of about 20 people rather than the 165 it had, and with an emphasis more on commentary, advice and links to other sites than on original reporting.

The 146-year-old Seattle Post-Intelligencer printed its last edition on Tuesday, becoming an Internet-only news source. In a report on its own Web site, the “paper” described the contours of the new, much smaller operation now in place. The P-I, as it’s called, is a “community platform” that will feature “breaking news, columns from prominent Seattle residents, community databases, photo galleries, 150 citizen bloggers and links to other journalistic outlets.” The New York Times notes that The P-I “will resemble a local Huffington Post more than a traditional newspaper,” with a news staff of about 20 people rather than the 165 it had, and with an emphasis more on commentary, advice and links to other sites than on original reporting.

The P-I venture may well fail — but in an essential way, that’s a good thing. Why that’s the case is explained in an indispensable essay posted by media-technology thinker Clay Shirky a few days ago. Glancing as far back as the 16th-century advent of the printing press, Shirky’s piece is an illuminating synthesis of the industry’s past and present — and, from where I’m sitting, brims with aphoristic insights pointing to a bright future for digital journalism. Original reporting in that realm — still much underdeveloped and ripe for innovation, in my view — will play a vital role in the further transformation.

Shirky writes: “People committed to saving newspapers [keep] demanding to know ‘If the old model is broken, what will work in its place?’ To which the answer is: Nothing. Nothing will work. There is no general model for newspapers to replace the one the internet just broke.”

To the old journalism guard, that’s a heartbreaking epilogue. Which of course misses the point. (Revolutions create a curious inversion of perception, Shirky notes.) “With the old economics destroyed, organizational forms perfected for industrial production have to be replaced with structures optimized for digital data,” he continues. “It makes increasingly less sense even to talk about a publishing industry, because the core problem publishing solves — the incredible difficulty, complexity, and expense of making something available to the public — has stopped being a problem.”

Revolution is a dramatic word, but it’s exactly what we’re witnessing, if in slow motion. It began a little more than a decade ago and perhaps will require another decade before reaching a level of maturity and stability with new form. Shirky describes the familiar process: “The old stuff gets broken faster than the new stuff is put in its place. The importance of any given experiment isn’t apparent at the moment it appears; big changes stall, small changes spread. Even the revolutionaries can’t predict what will happen.”

(On recognizing “the importance of any given experiment,” see Shirky’s great distillation of the rise of Craigslist. Experiments are only revealed in retrospect to be turning points, he observes. And regarding “big changes stall” — the fashionable HuffPo model, anyone? With all due respect and admiration for its achievements during an epic election year, who really believes HuffPo’s almost-zero-reporting approach is the future of journalism?)

On with the greater experimentation and innovation, then. Many new attempts like The P-I probably will fail, and, in effect, we need them too. “There is one possible answer,” Shirky says, “to the question ‘If the old model is broken, what will work in its place?’ The answer is: Nothing will work, but everything might.”

Comments (1)

Comments (1)

You must be logged in to post a comment.